Home

eBook (1) Marie only

|

|

(last updated on 2019/06/16: on

"去美亚买书指南" --- How to purchase this book on www.amazon.com )

|

|

|

|

|

Here is the easiest way to purchase yourst kindle book, including “Tang Poems” or any other book at the US Amazon store and read it on your PC, Laptop, Mac, iPhone, iPad, Android phone, etc. You don’t even have to download any Kindle Applications or purchase any Amazon Kindle Readers/devices. It also provides special instructions for people located in China or certain other foreign countries. The book is published at Amazon.com. |

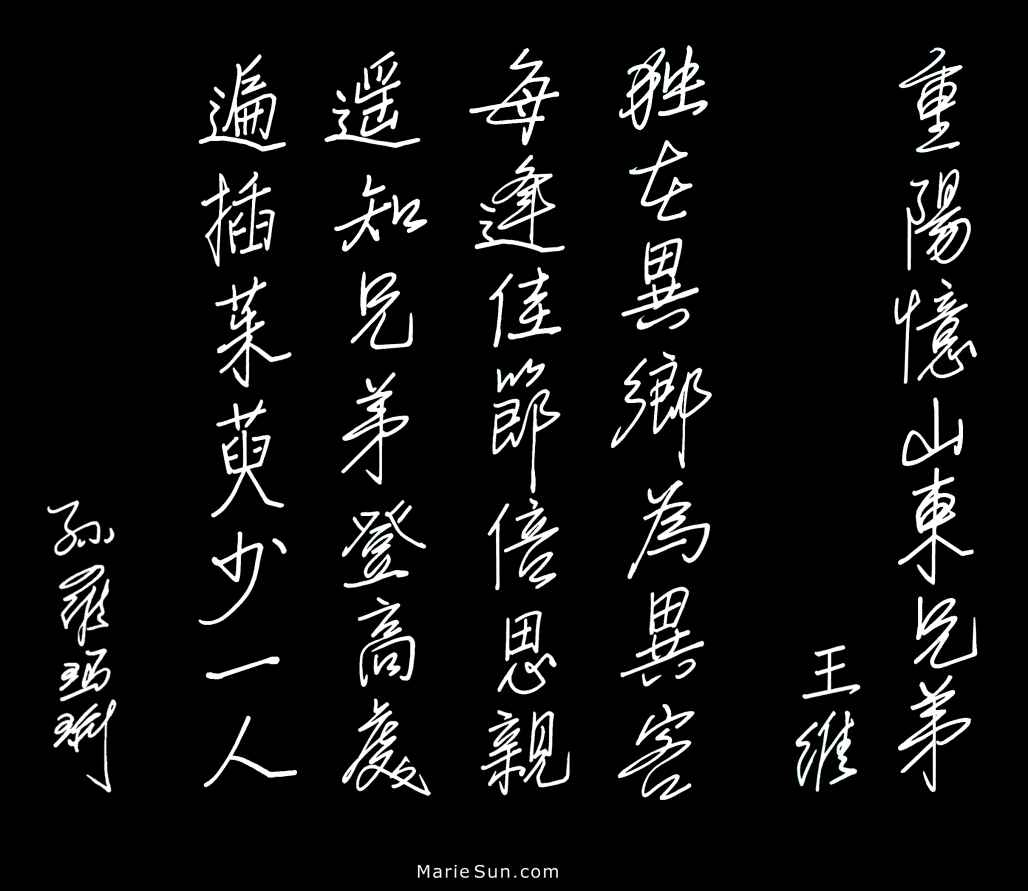

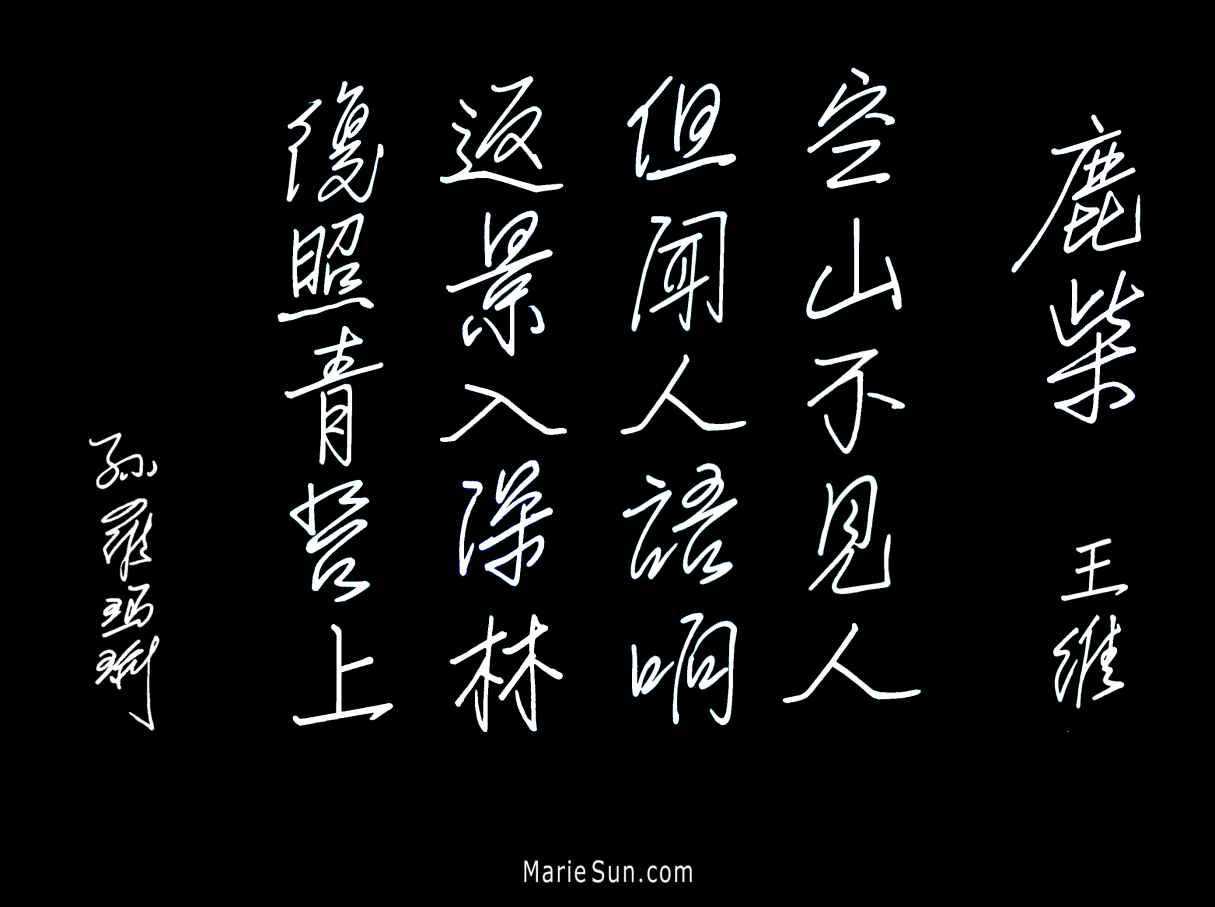

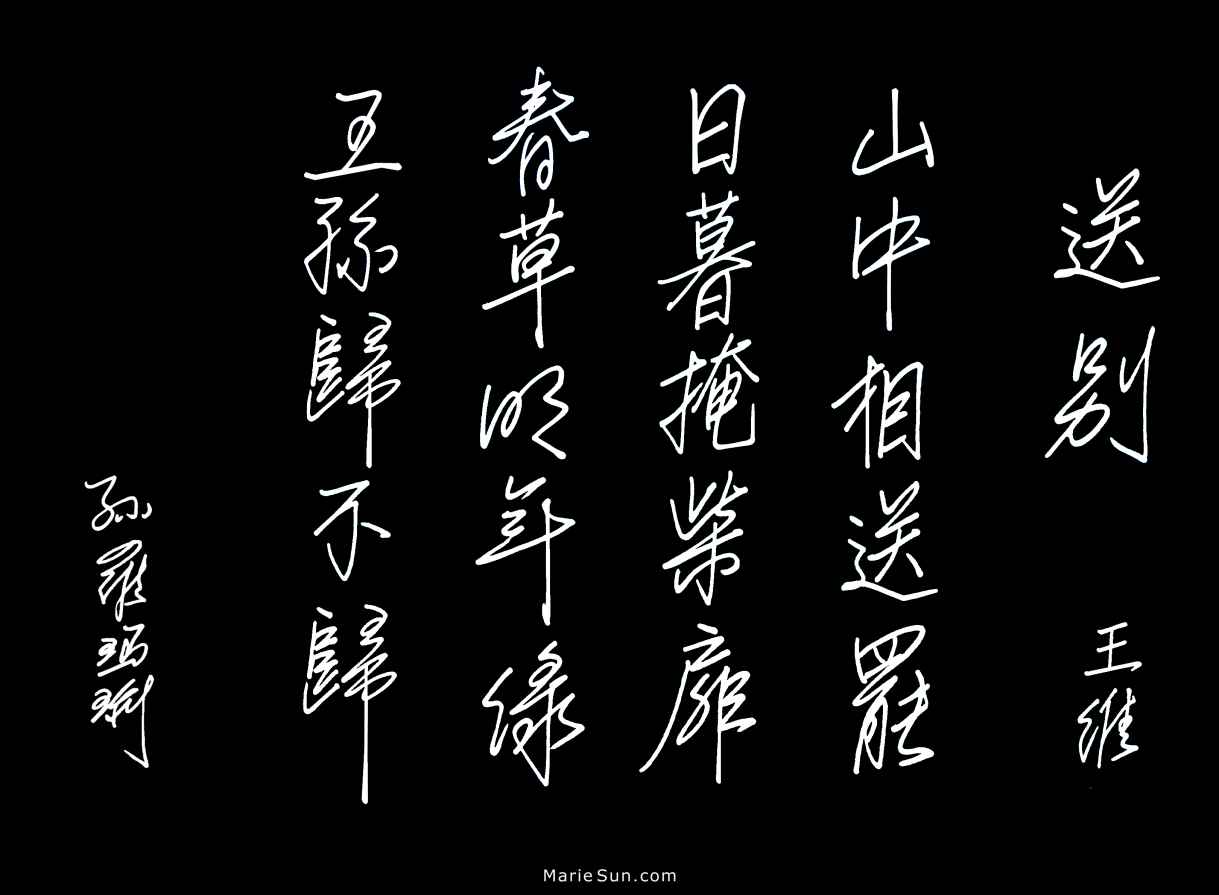

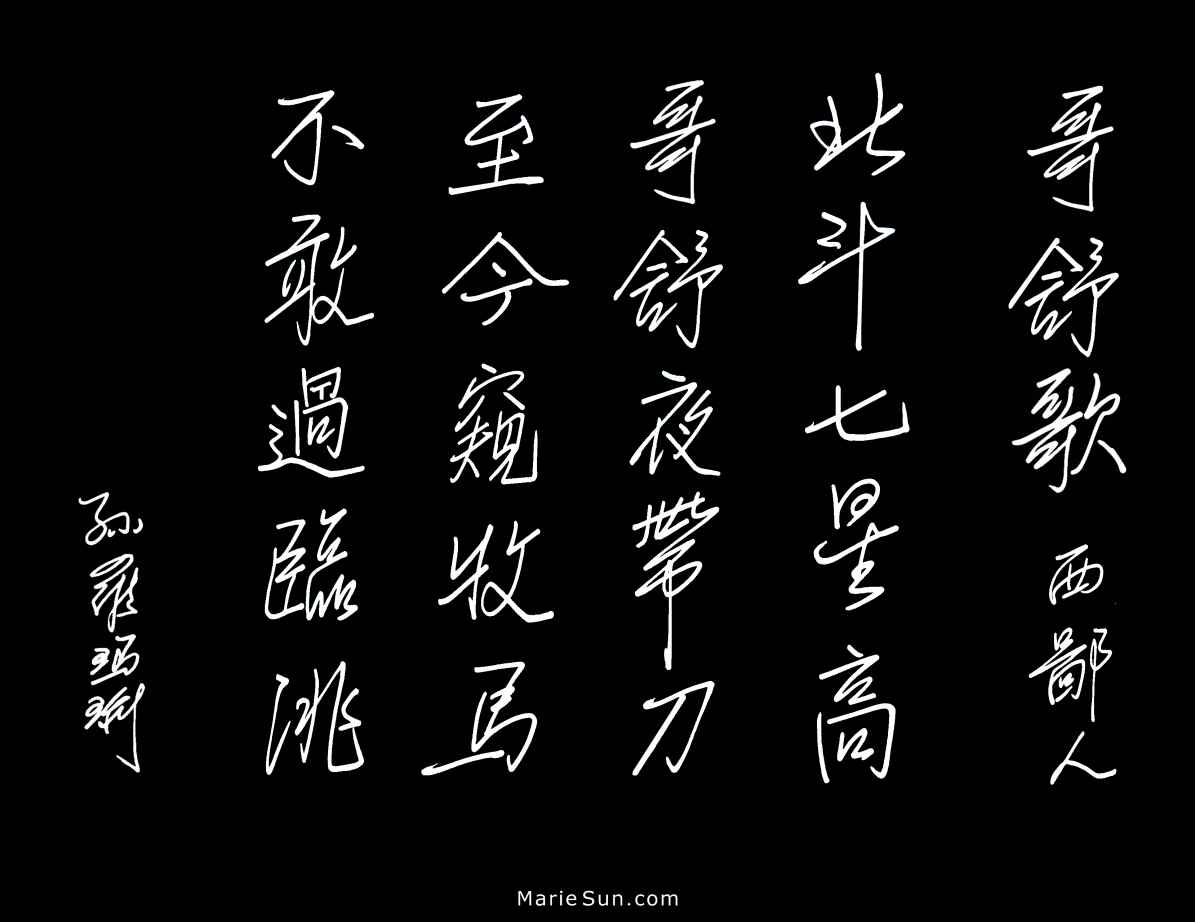

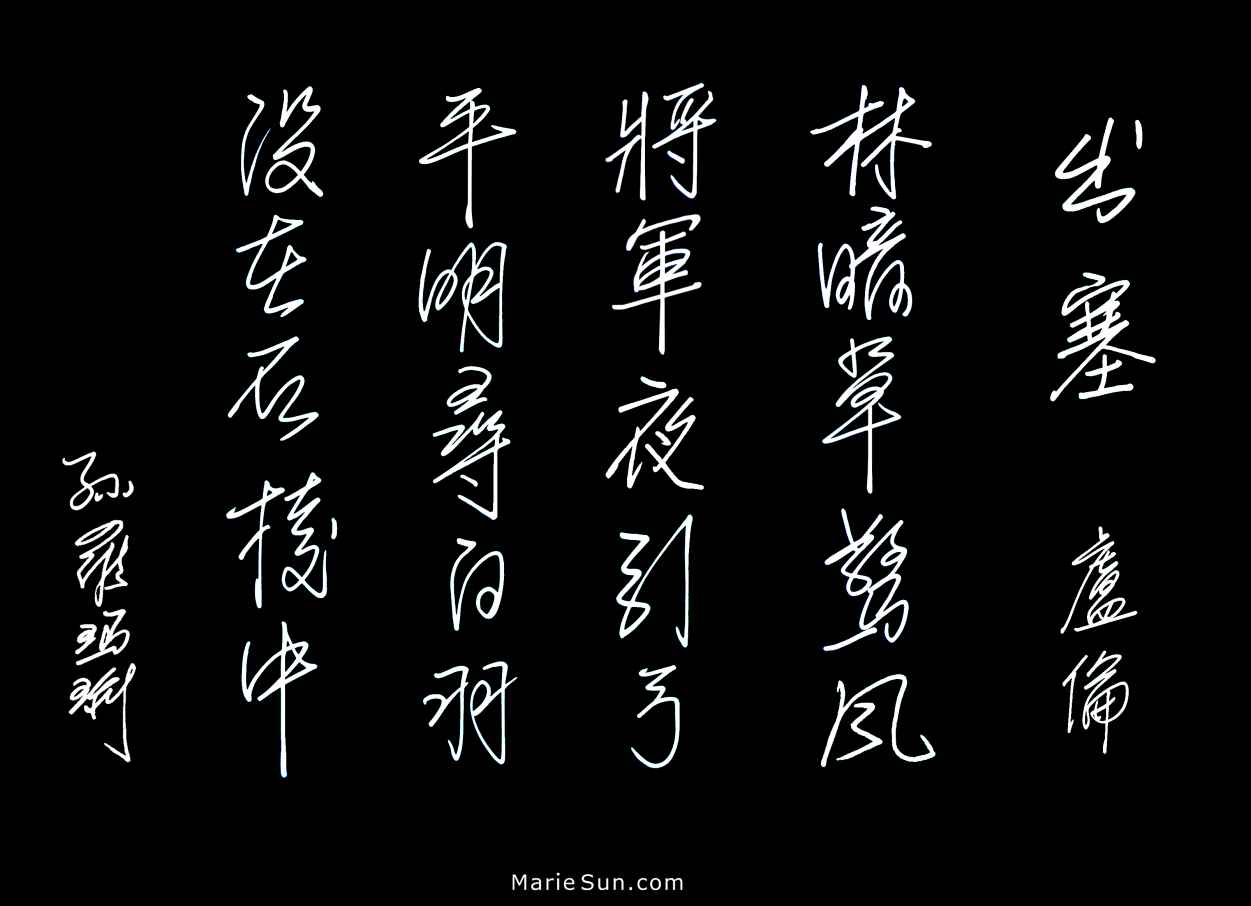

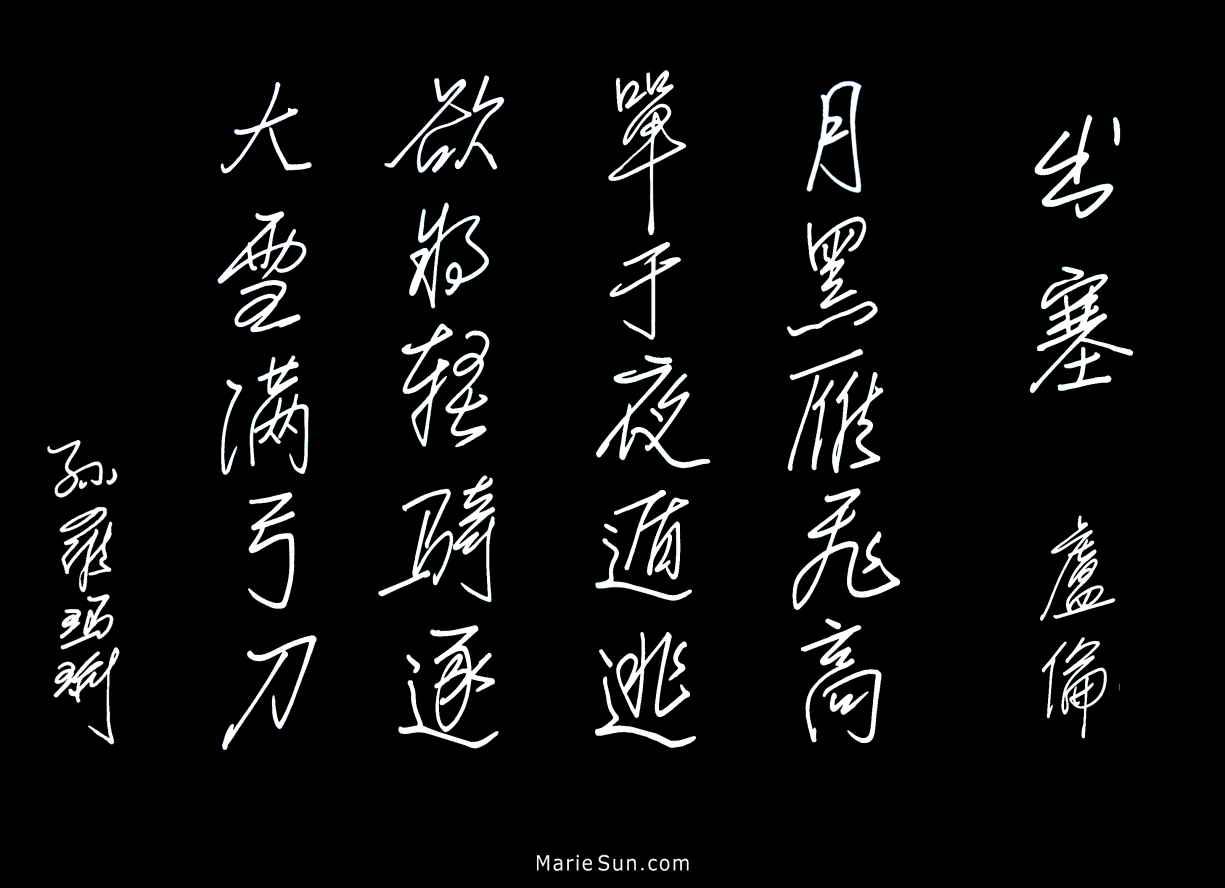

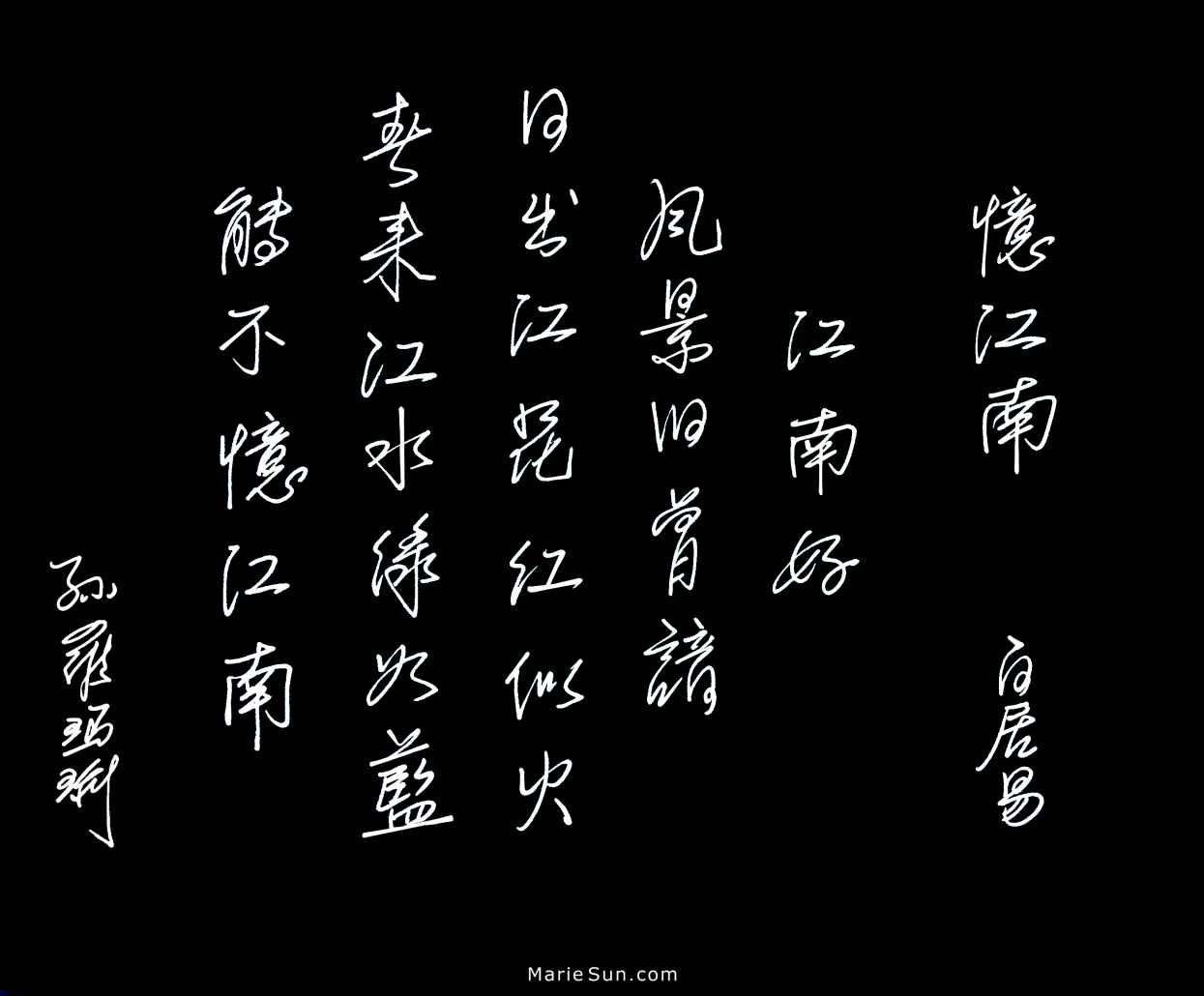

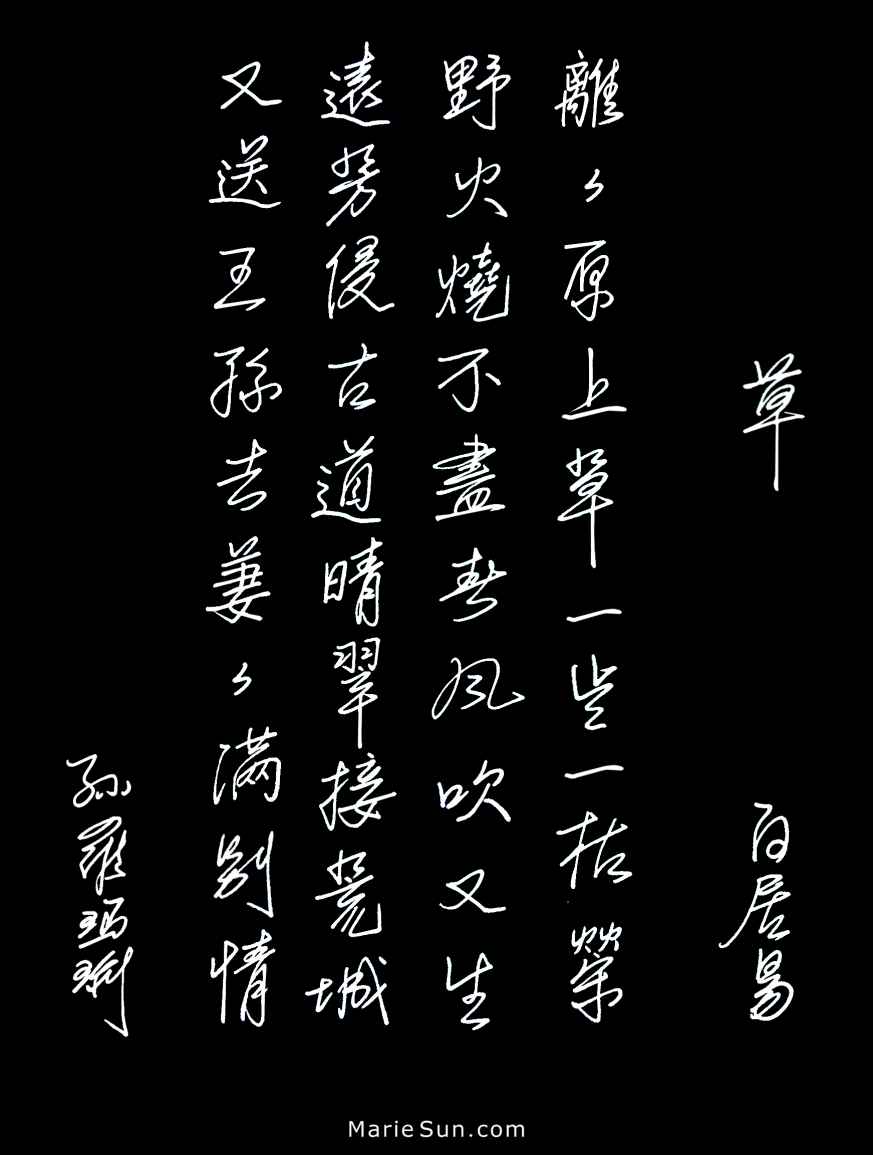

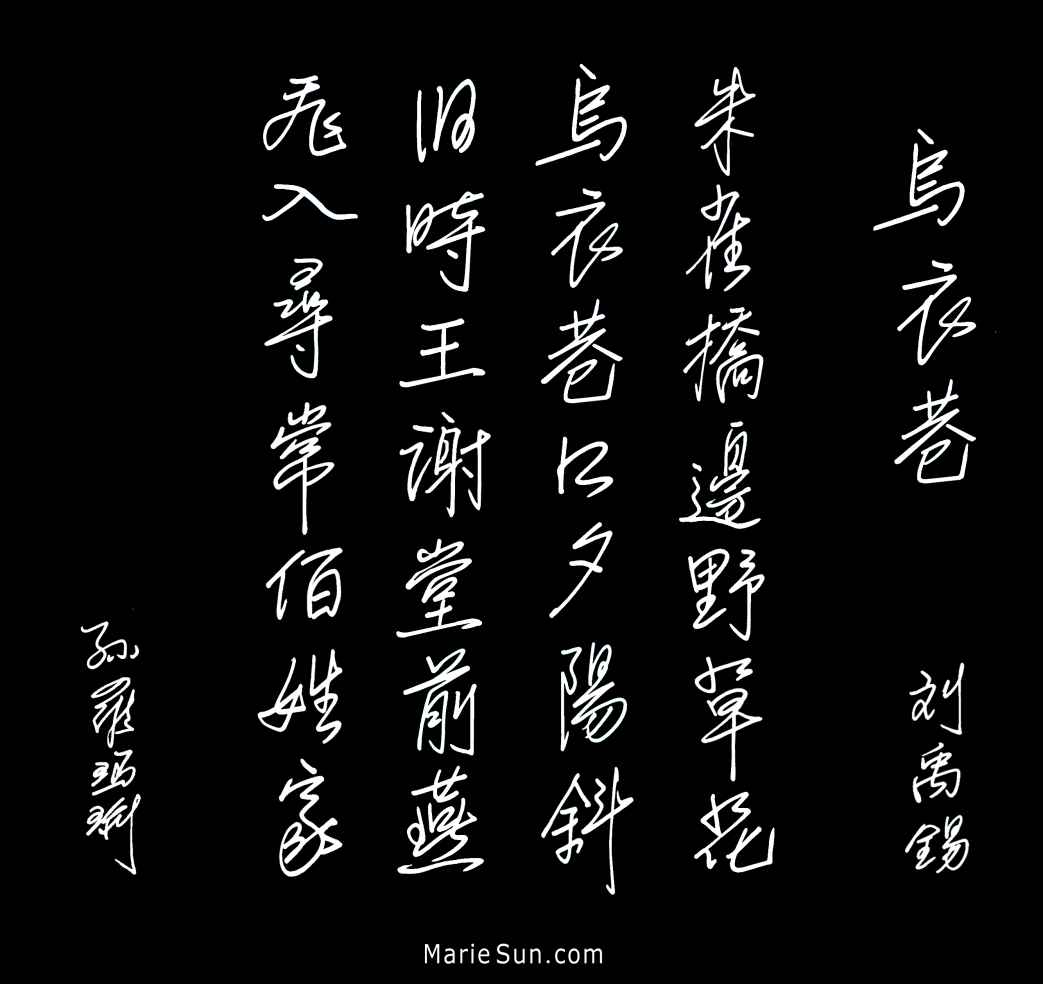

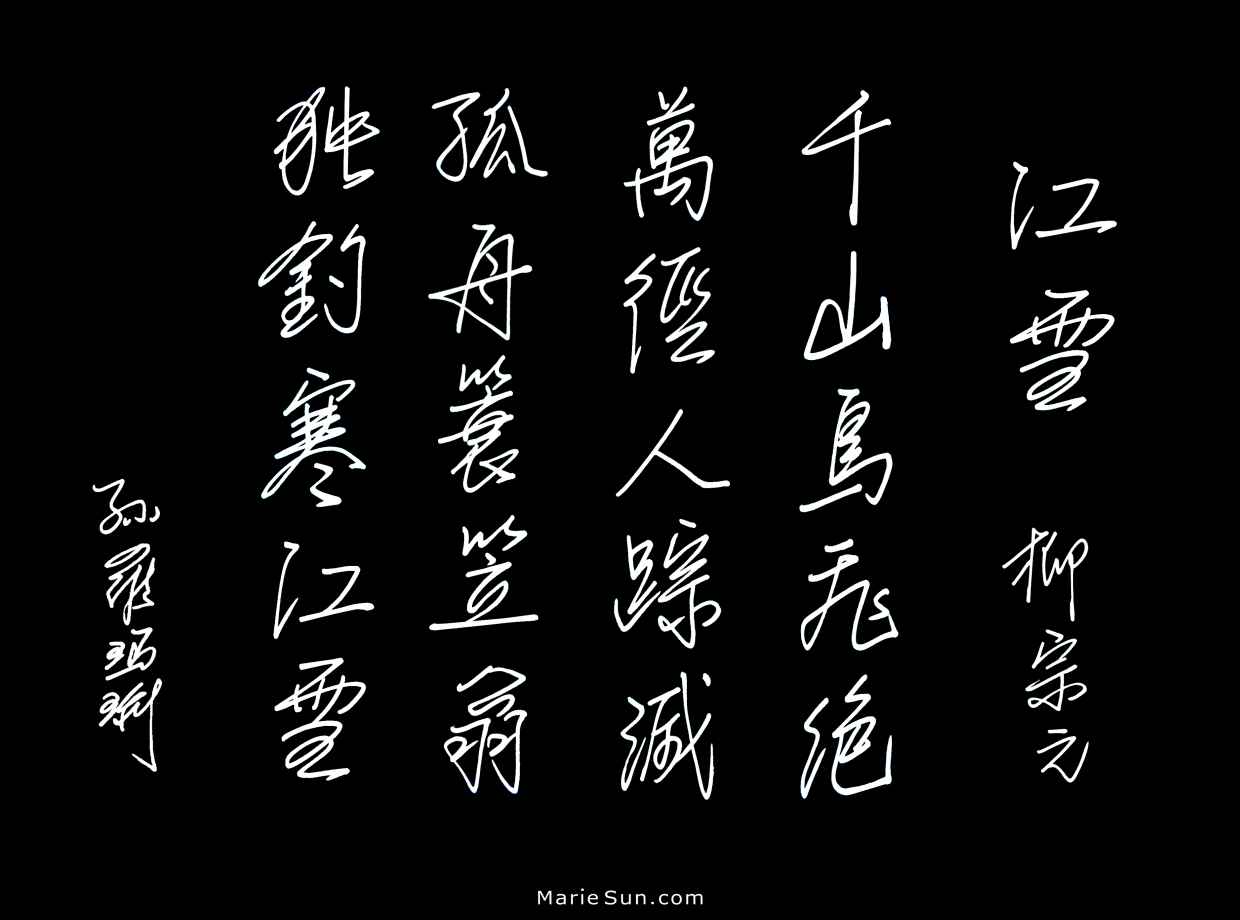

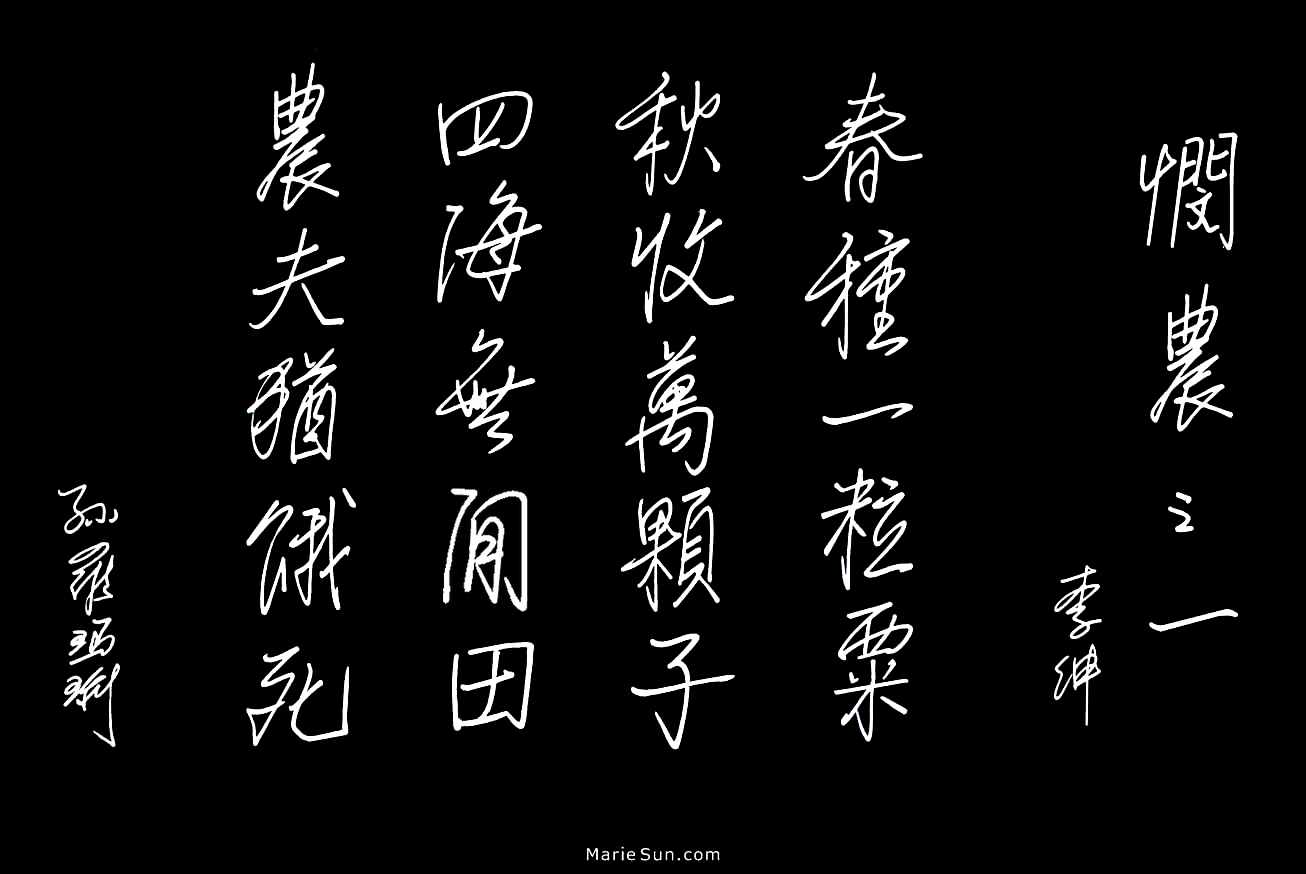

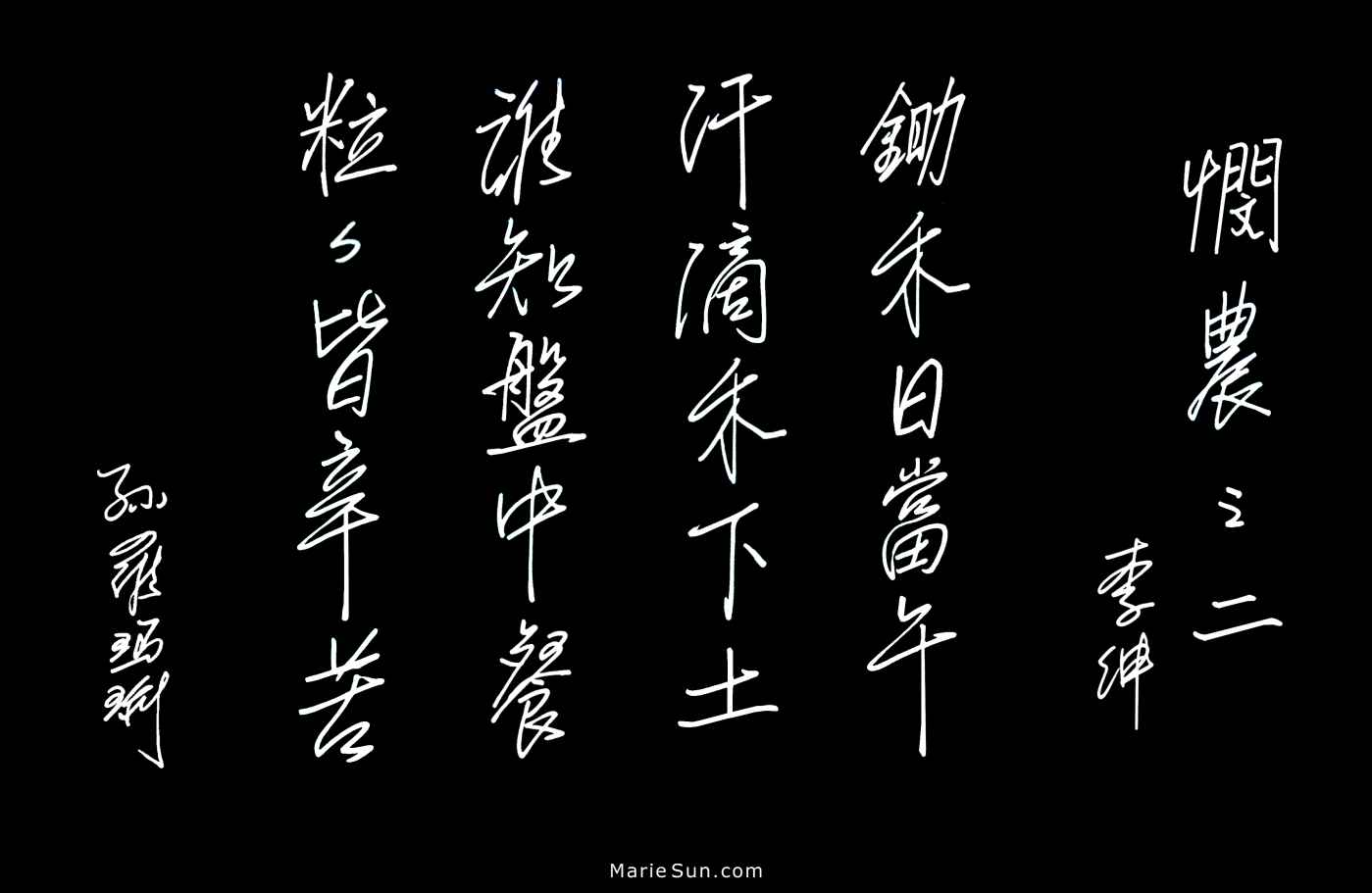

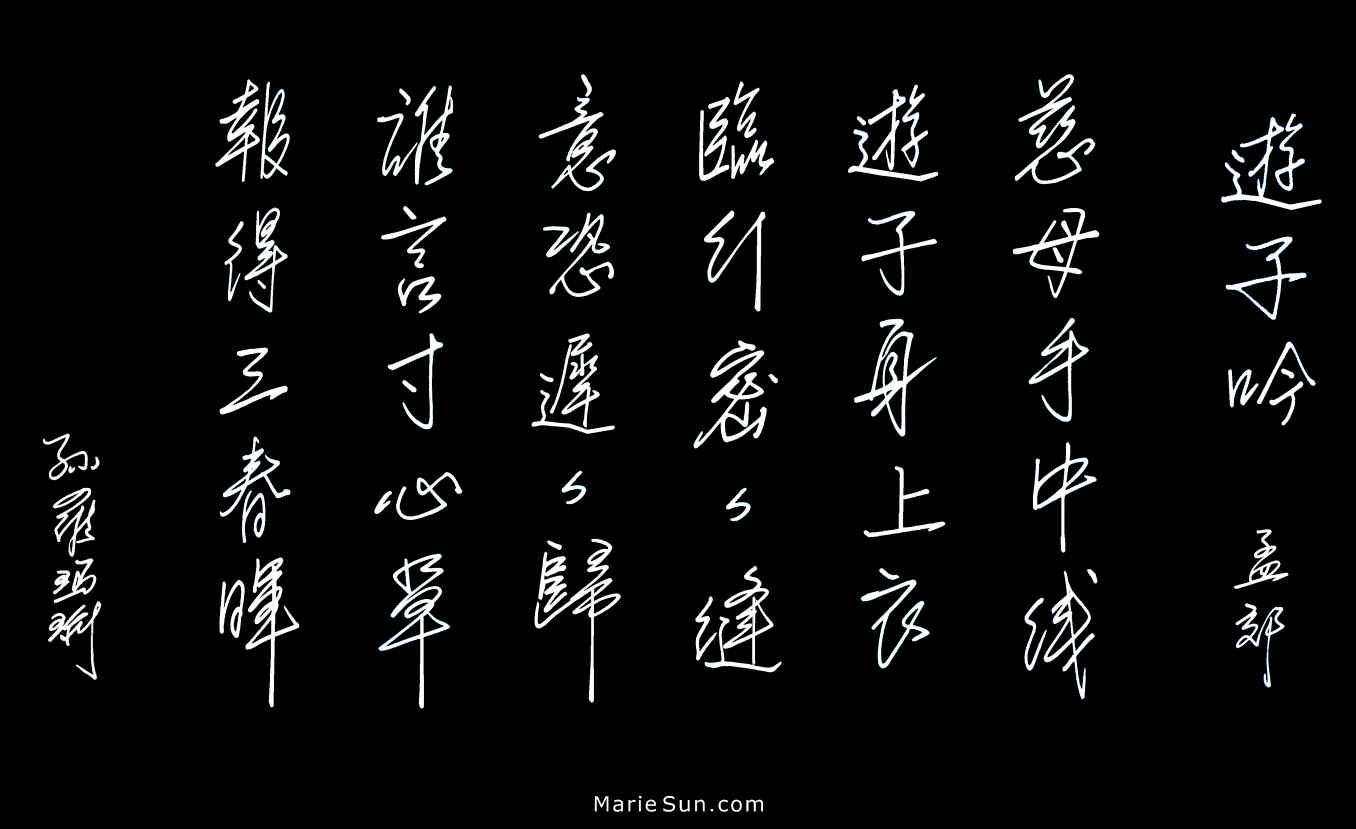

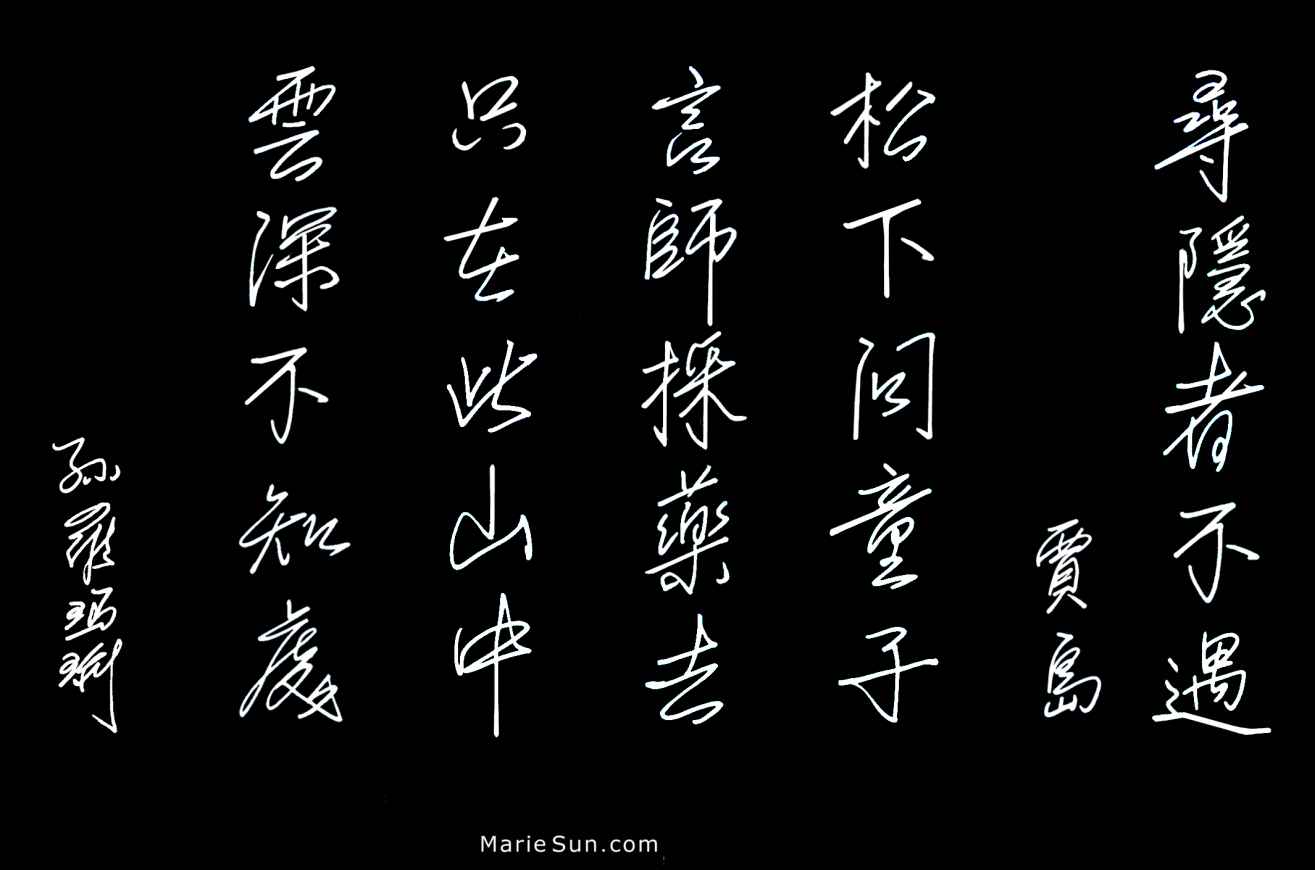

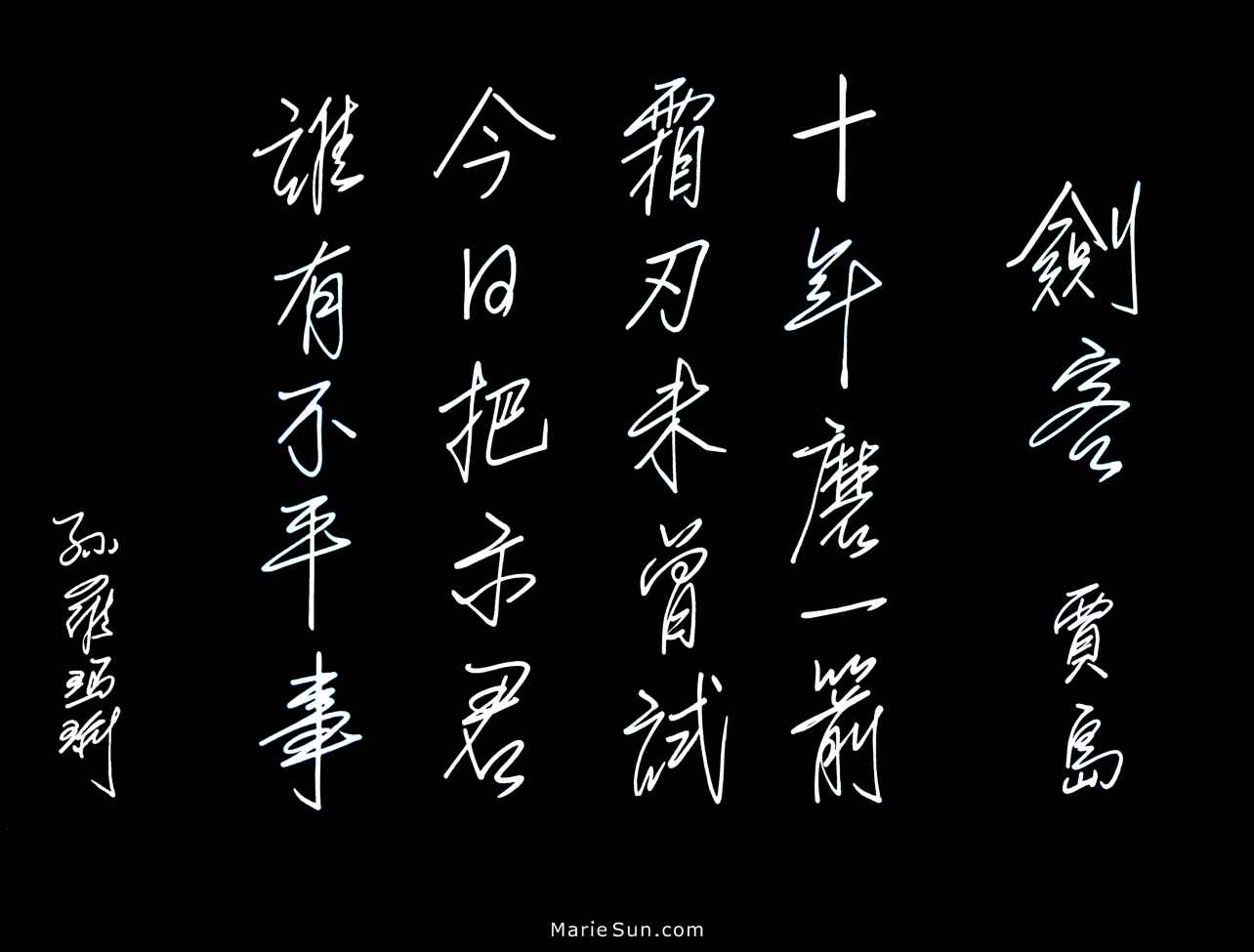

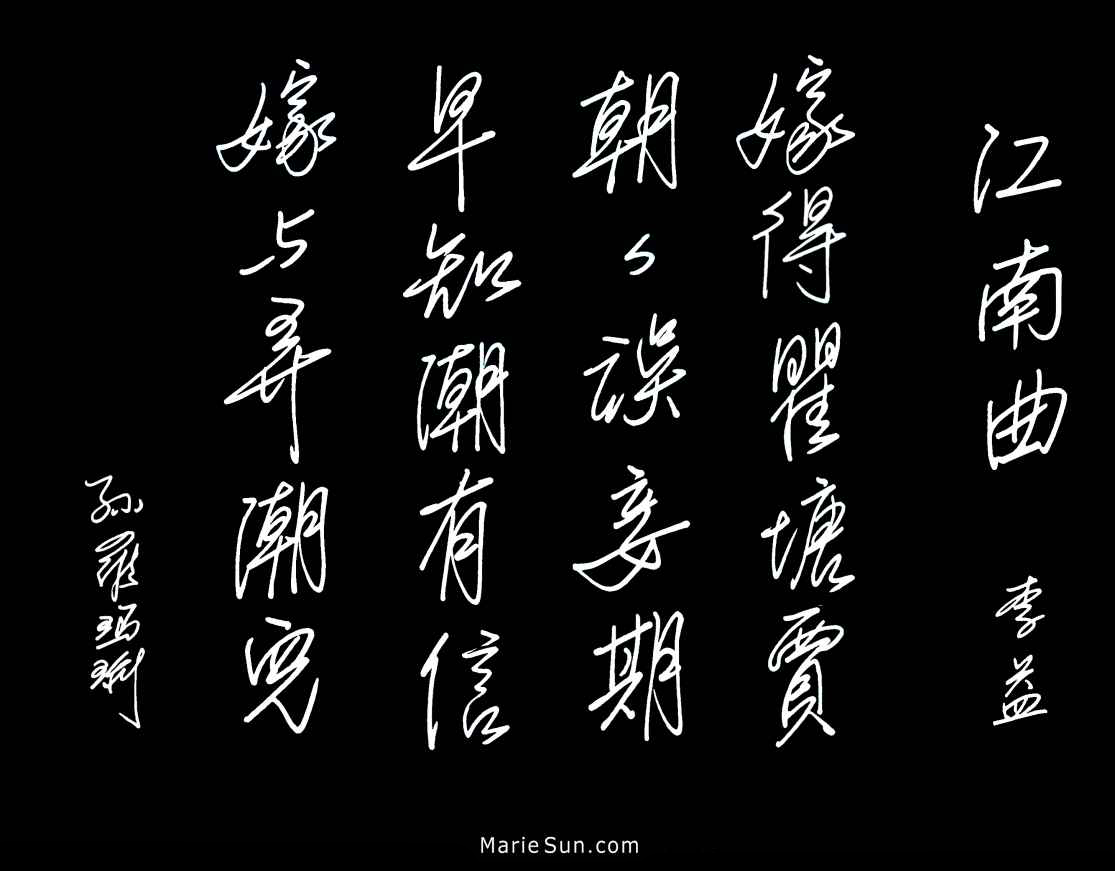

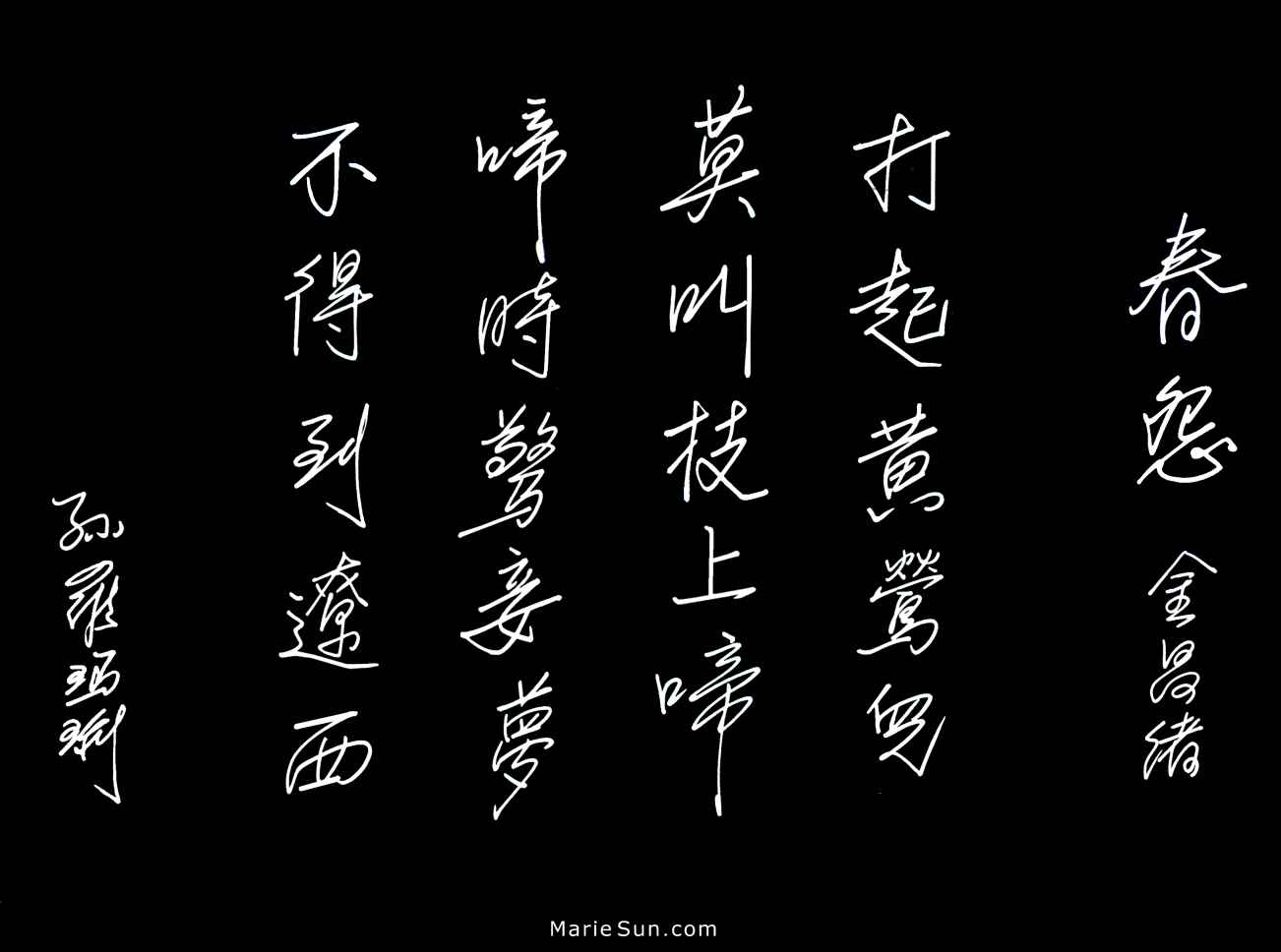

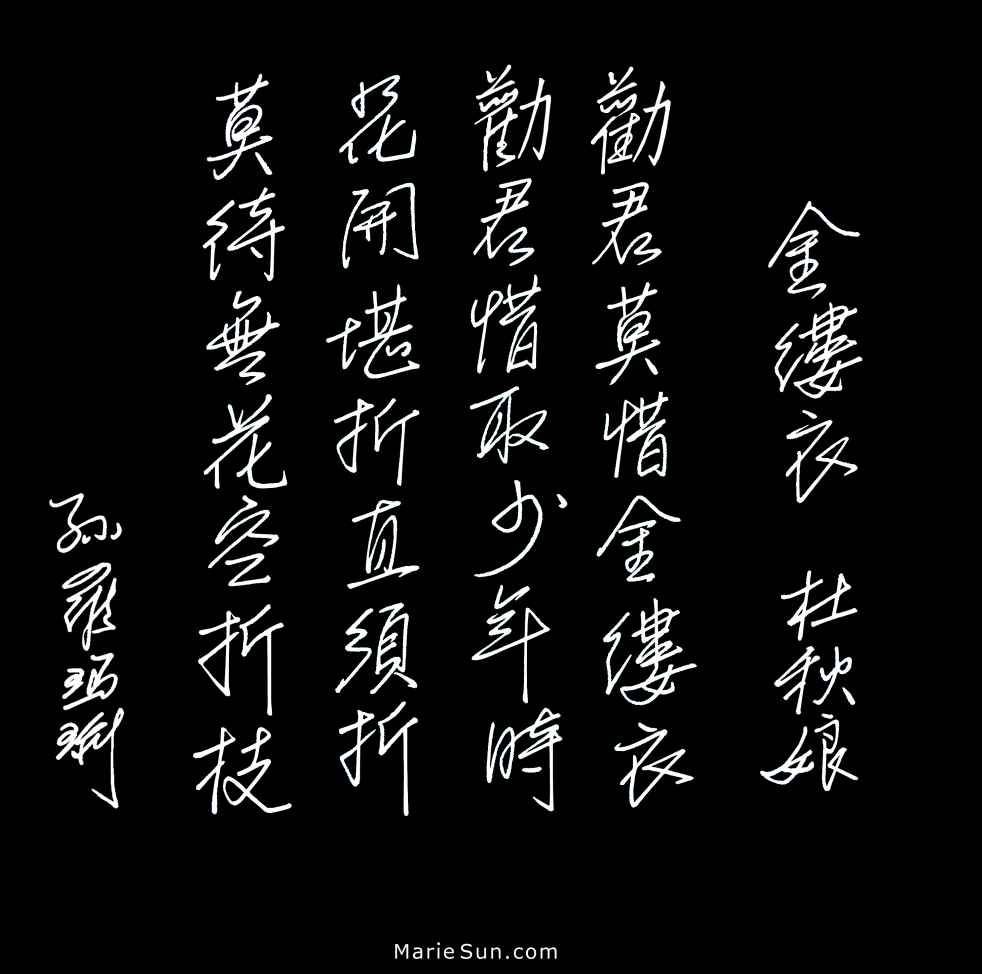

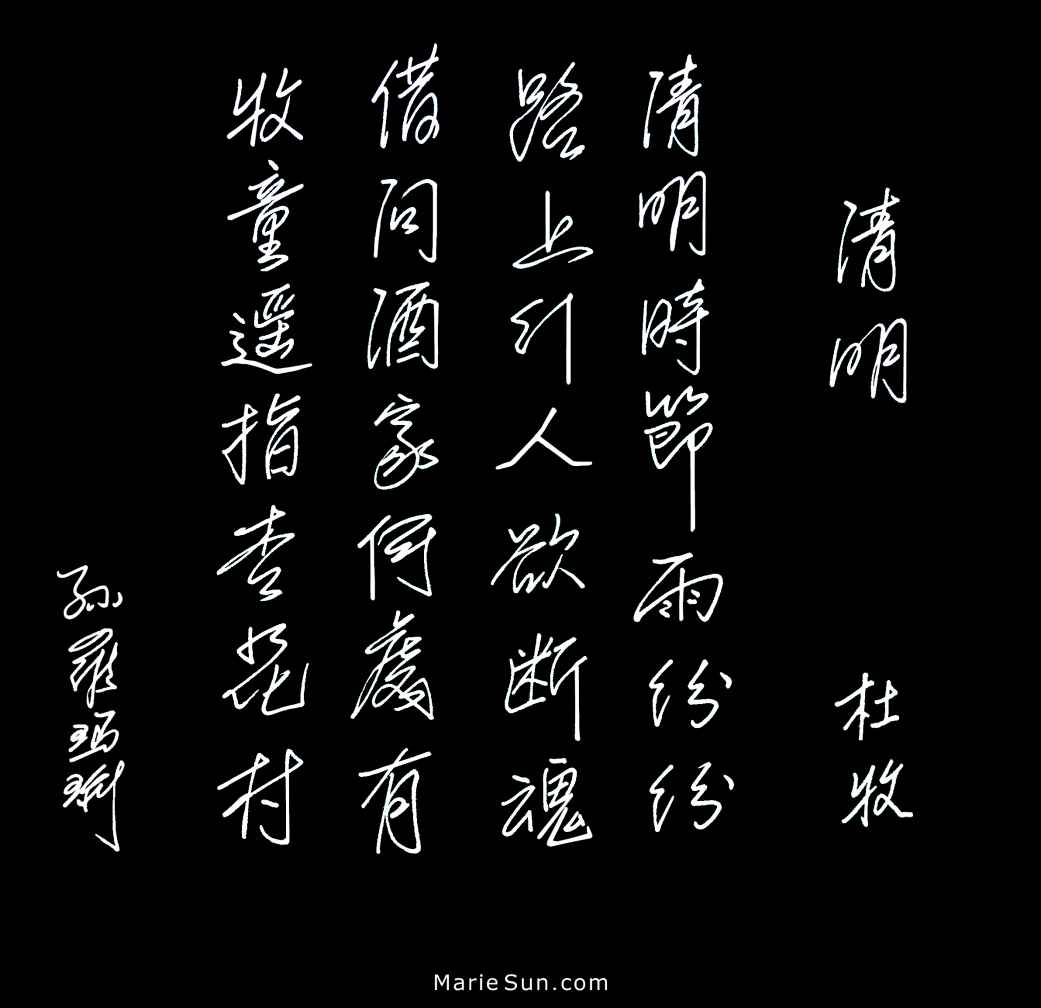

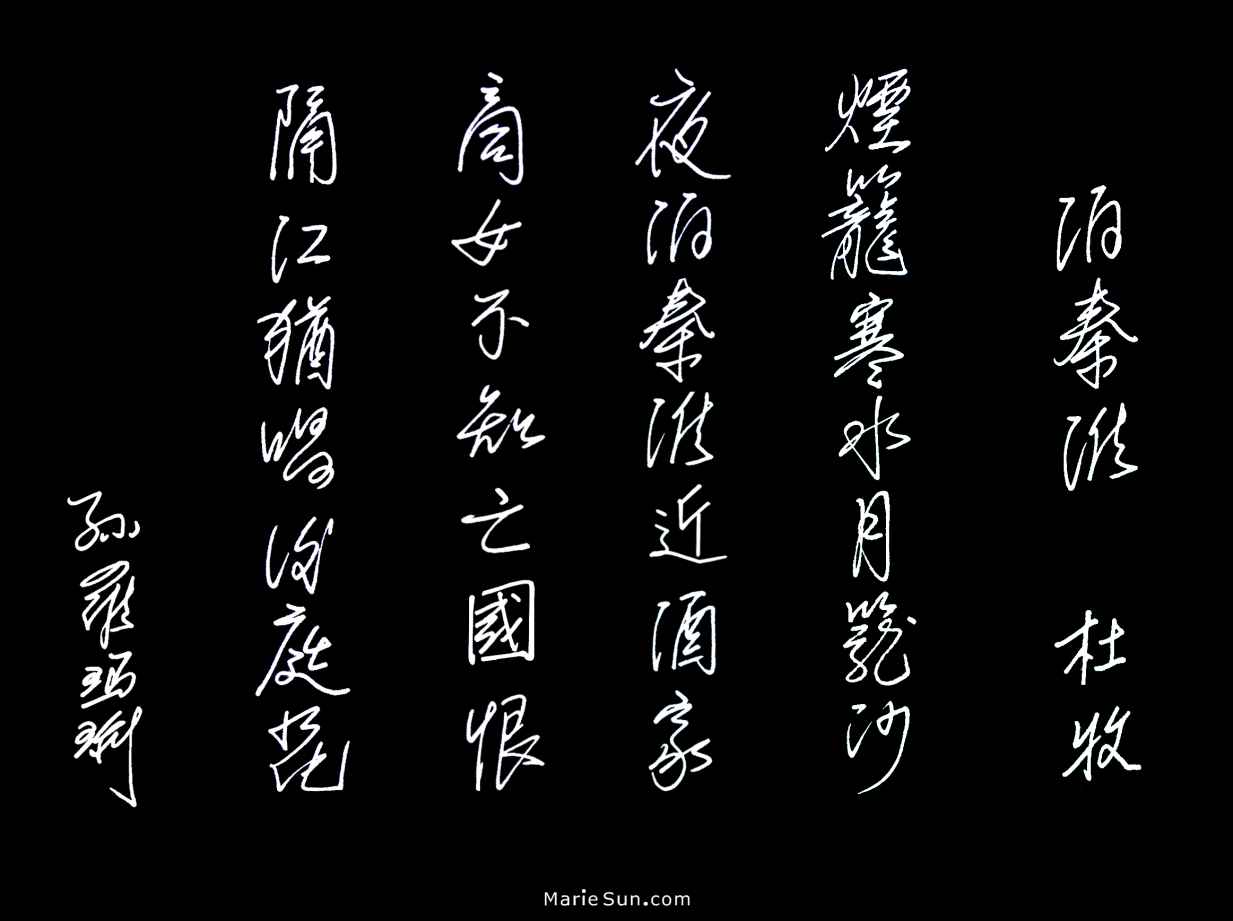

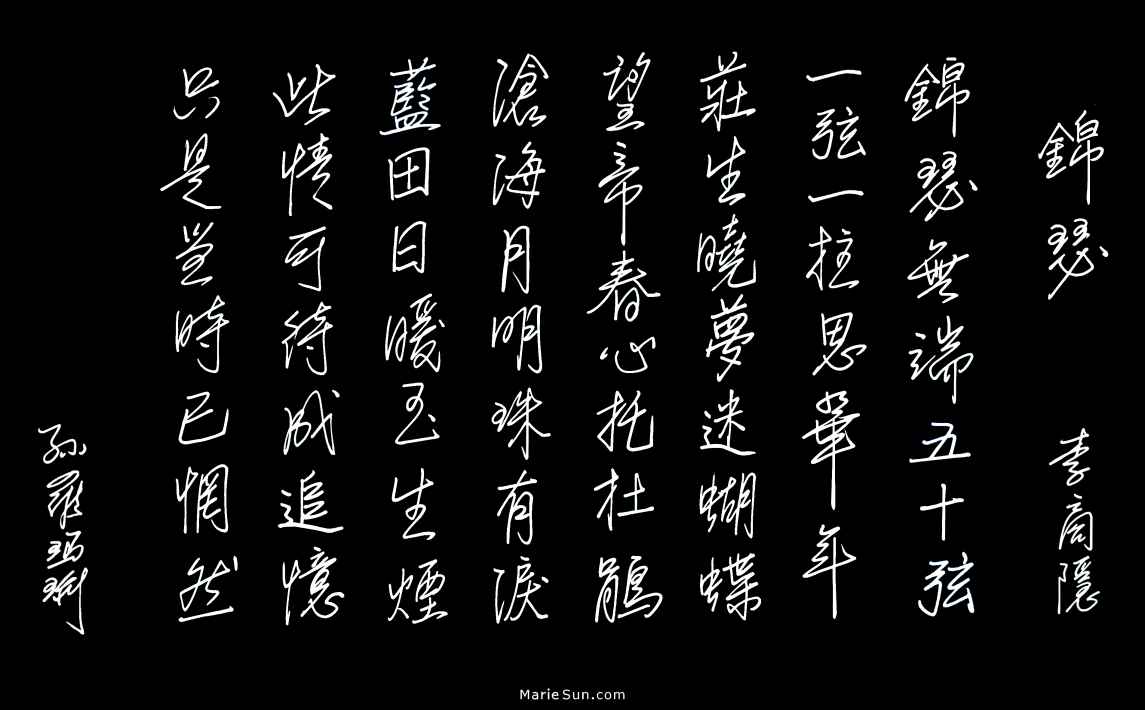

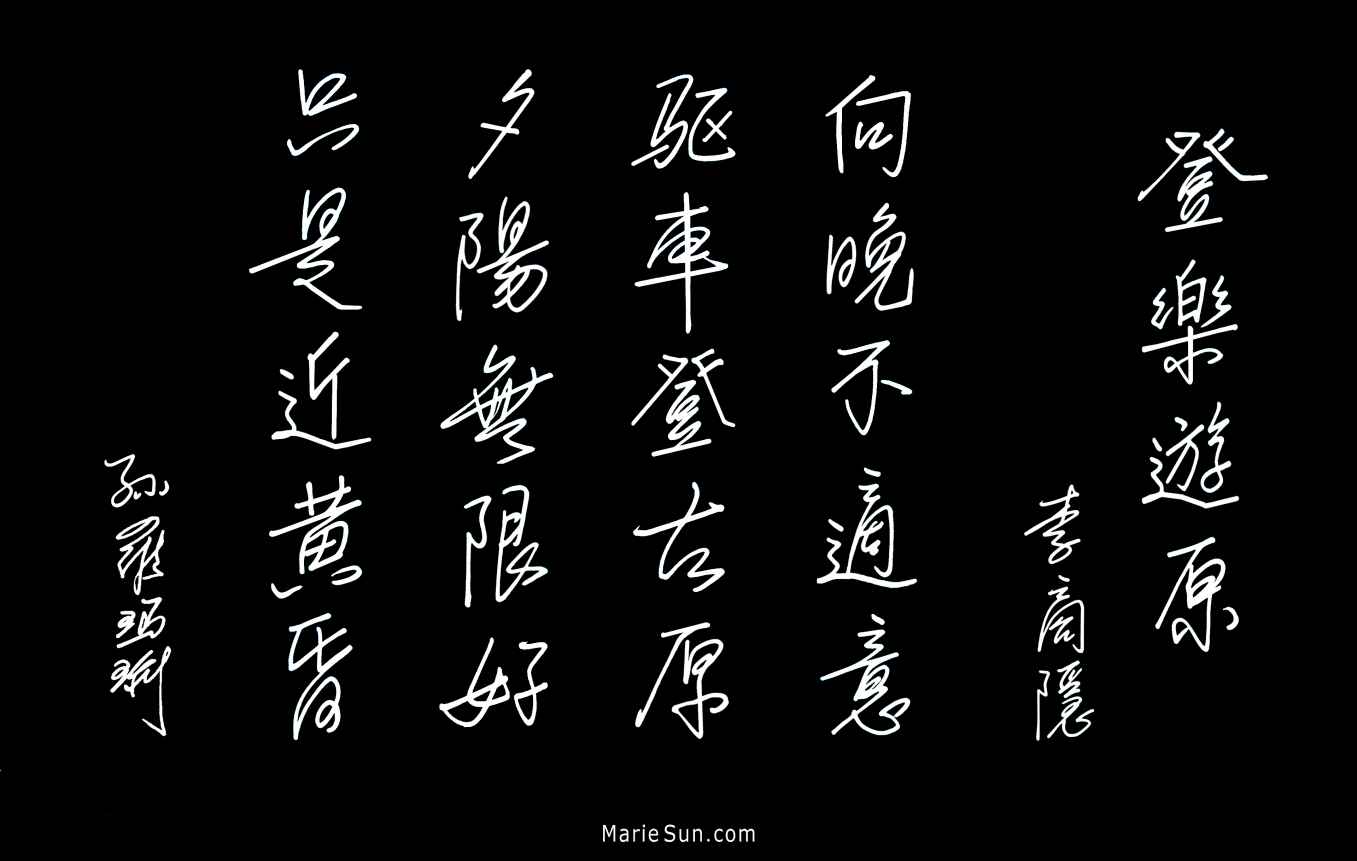

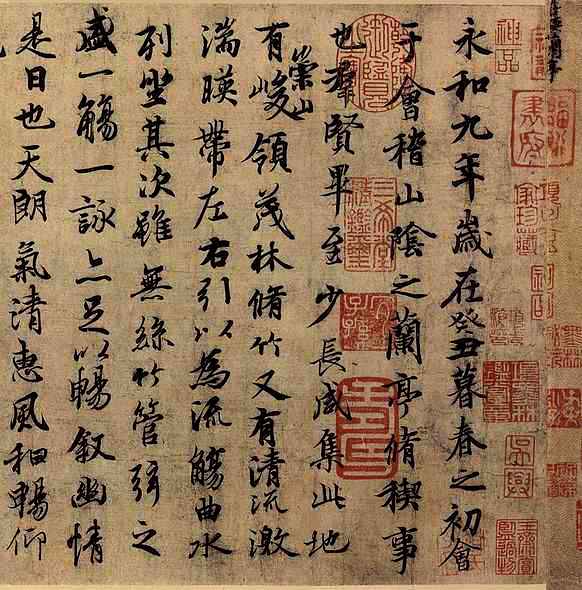

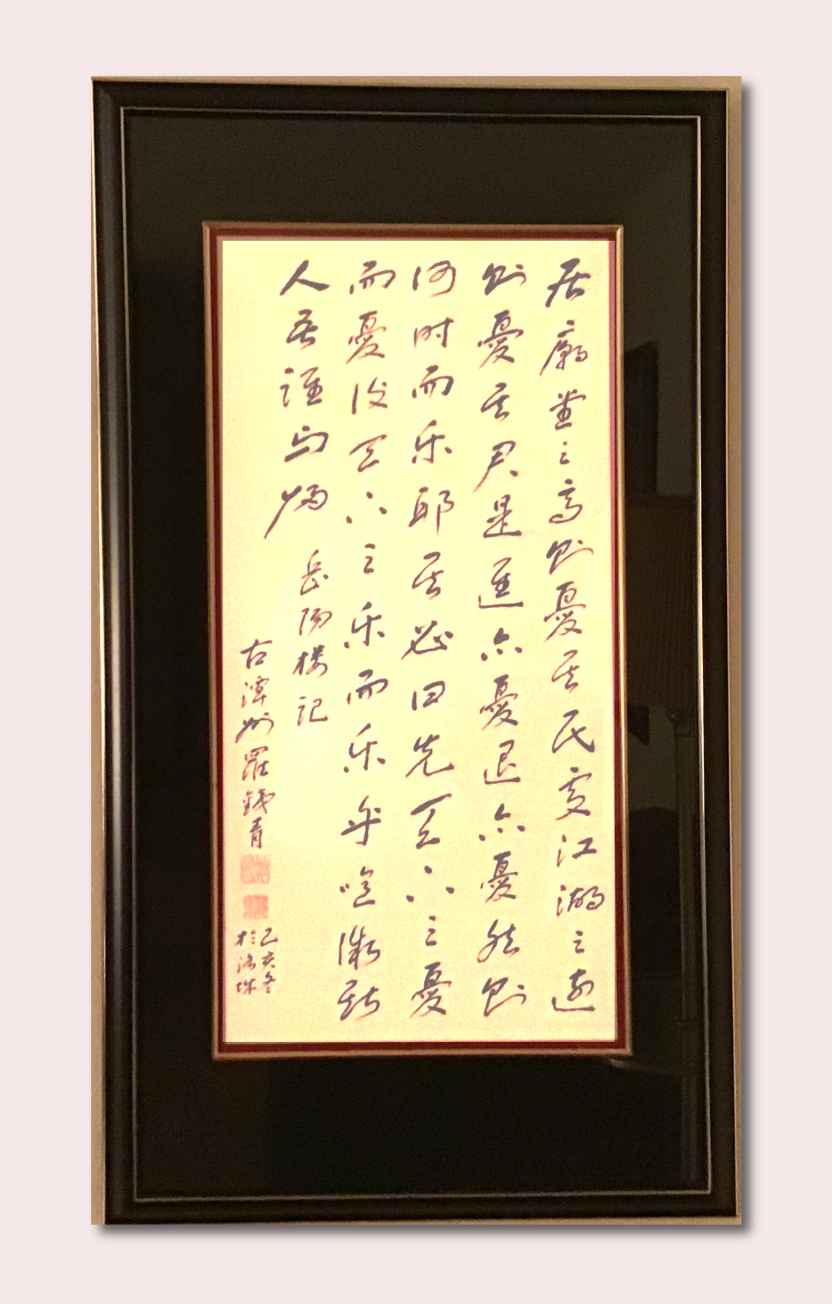

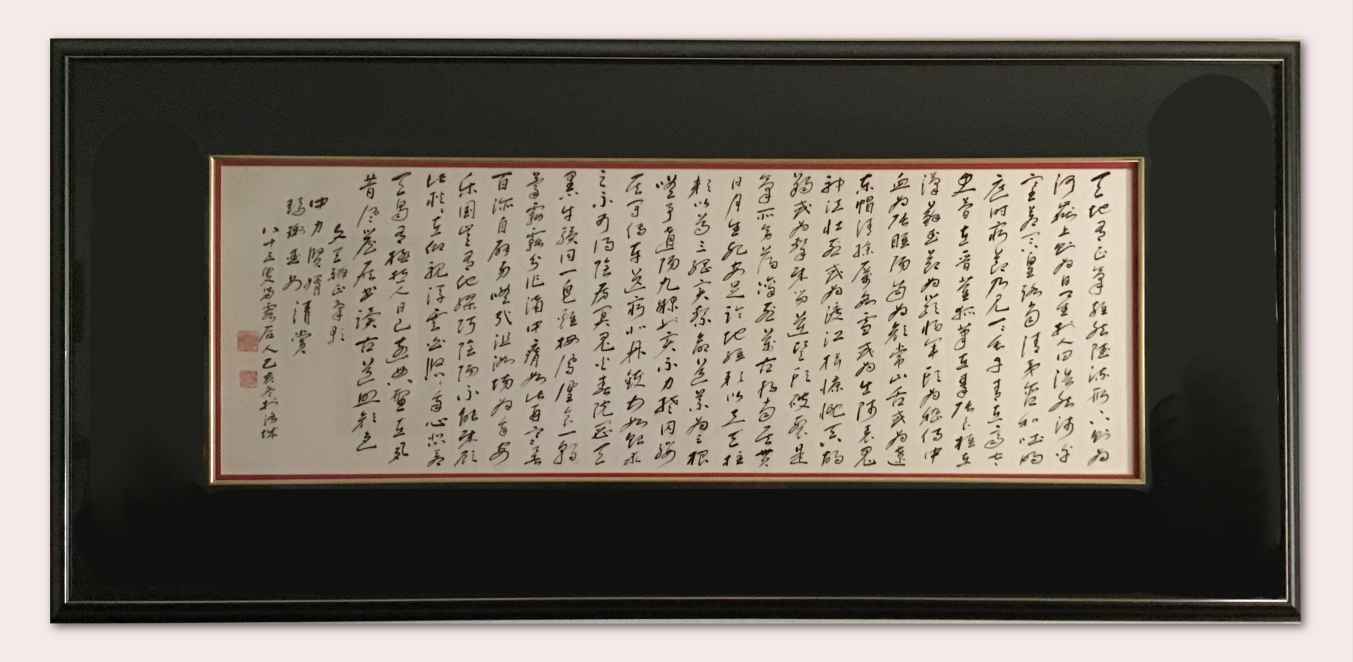

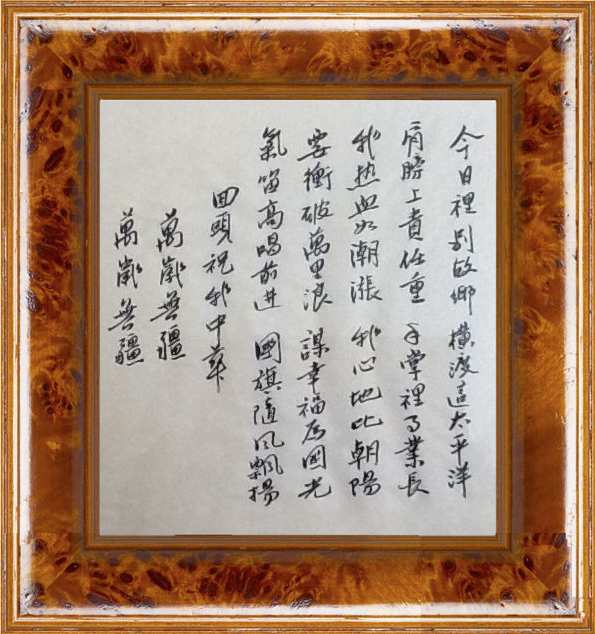

Calligraphy in xingshu 行书 style

|

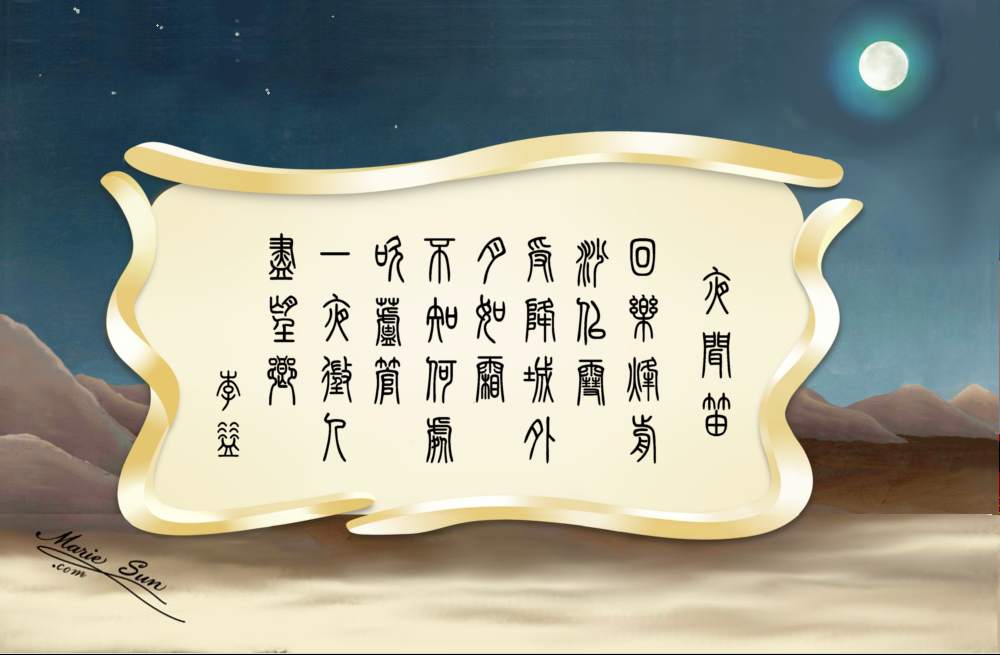

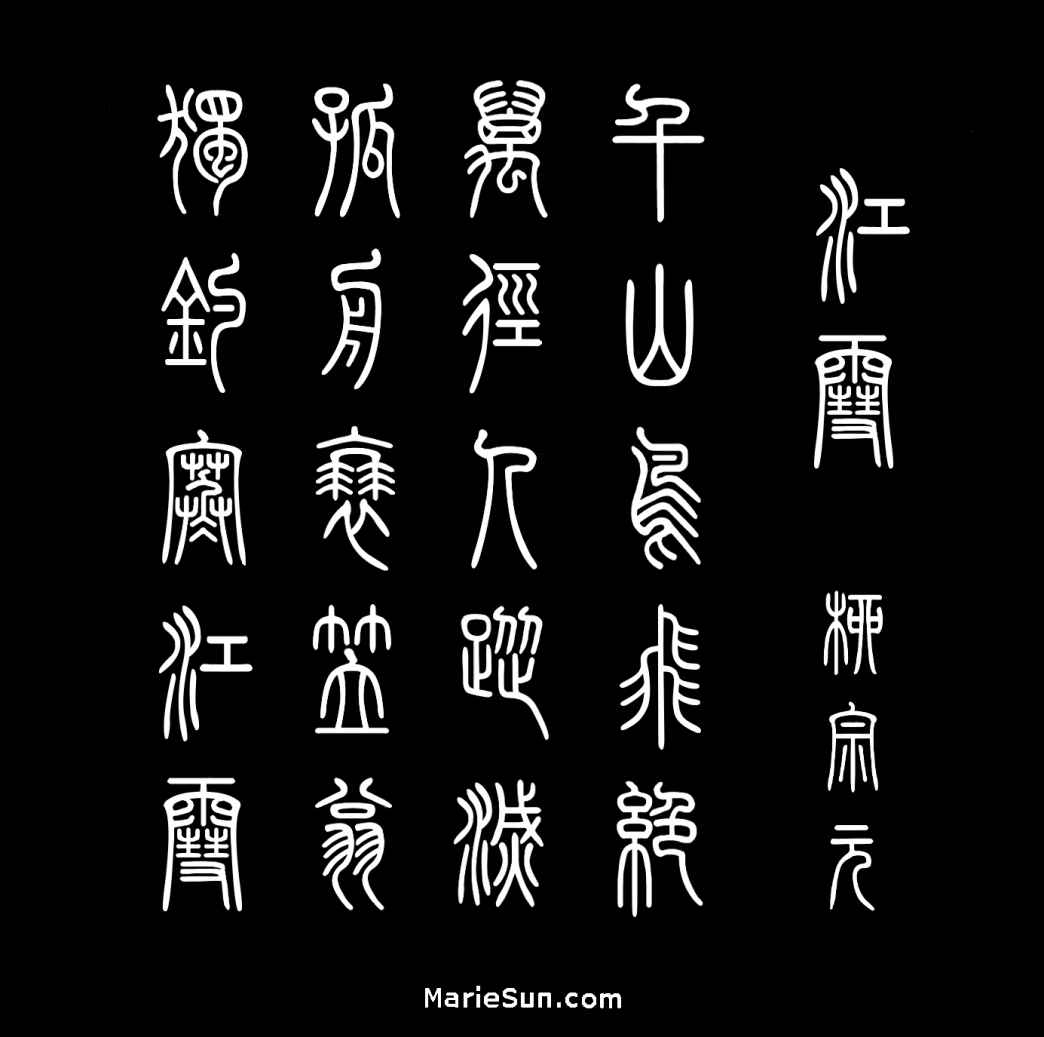

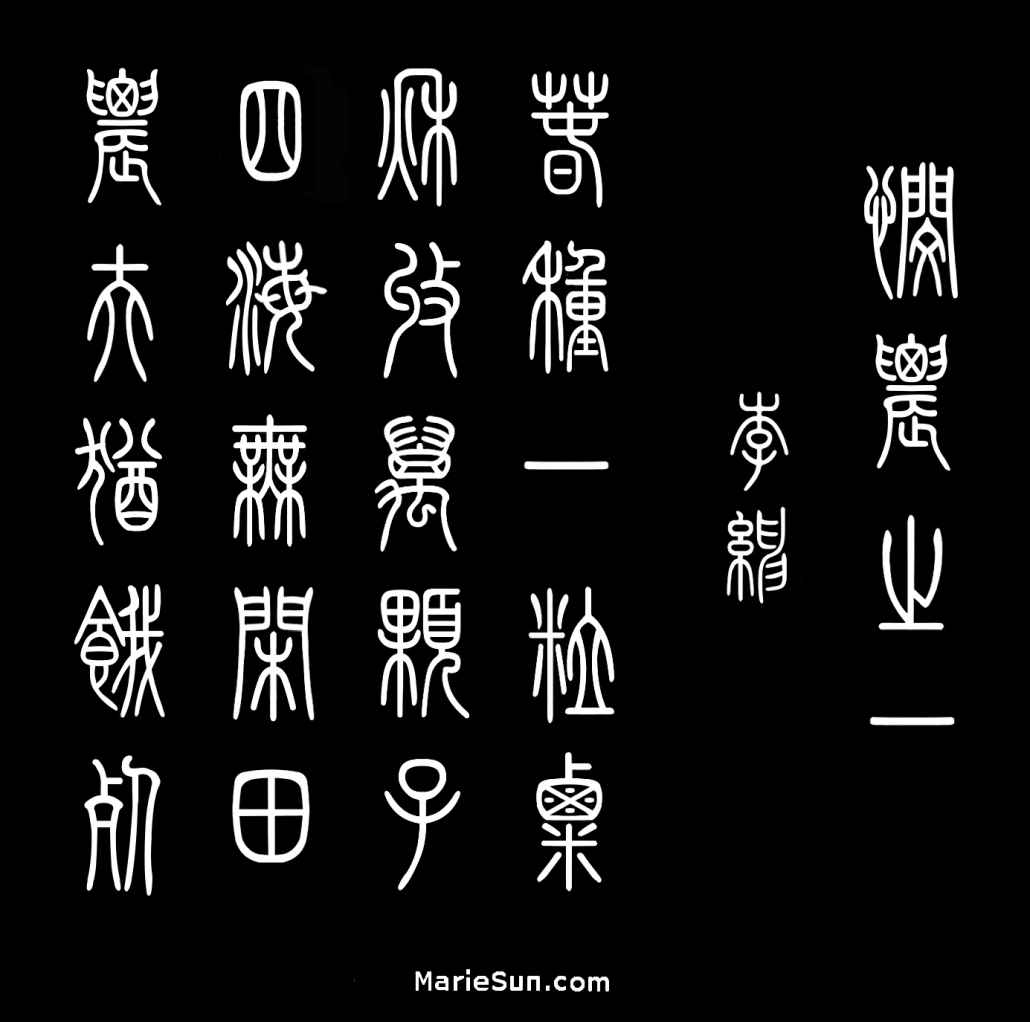

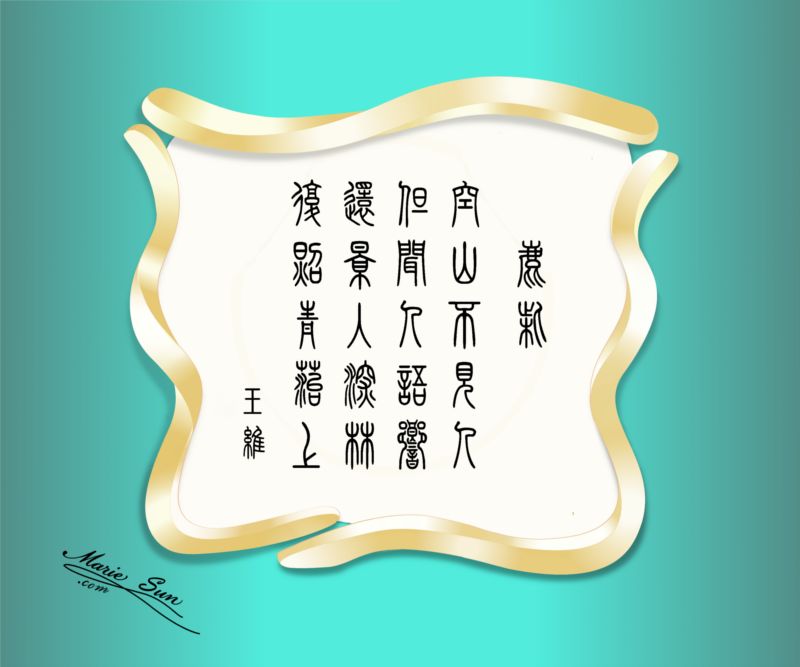

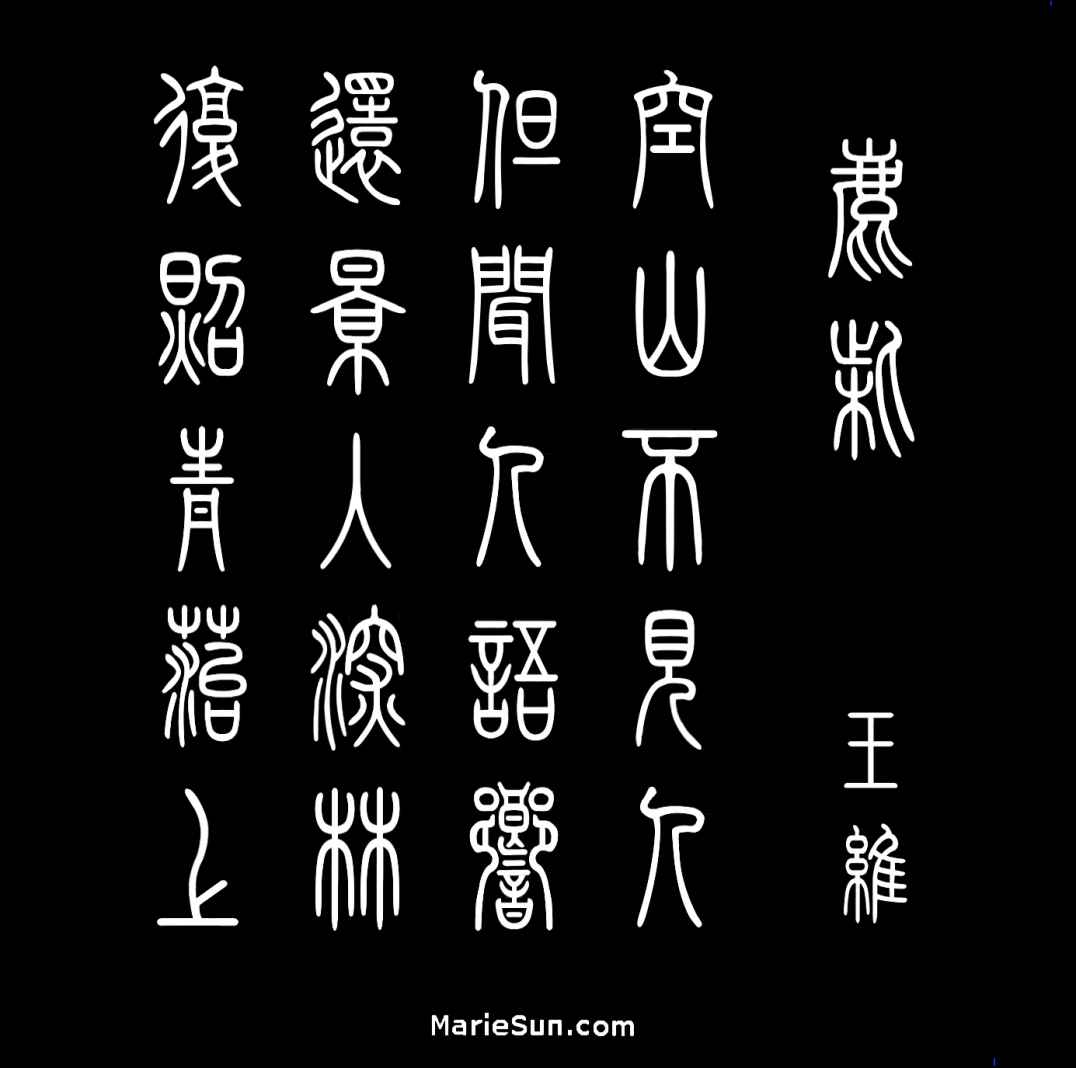

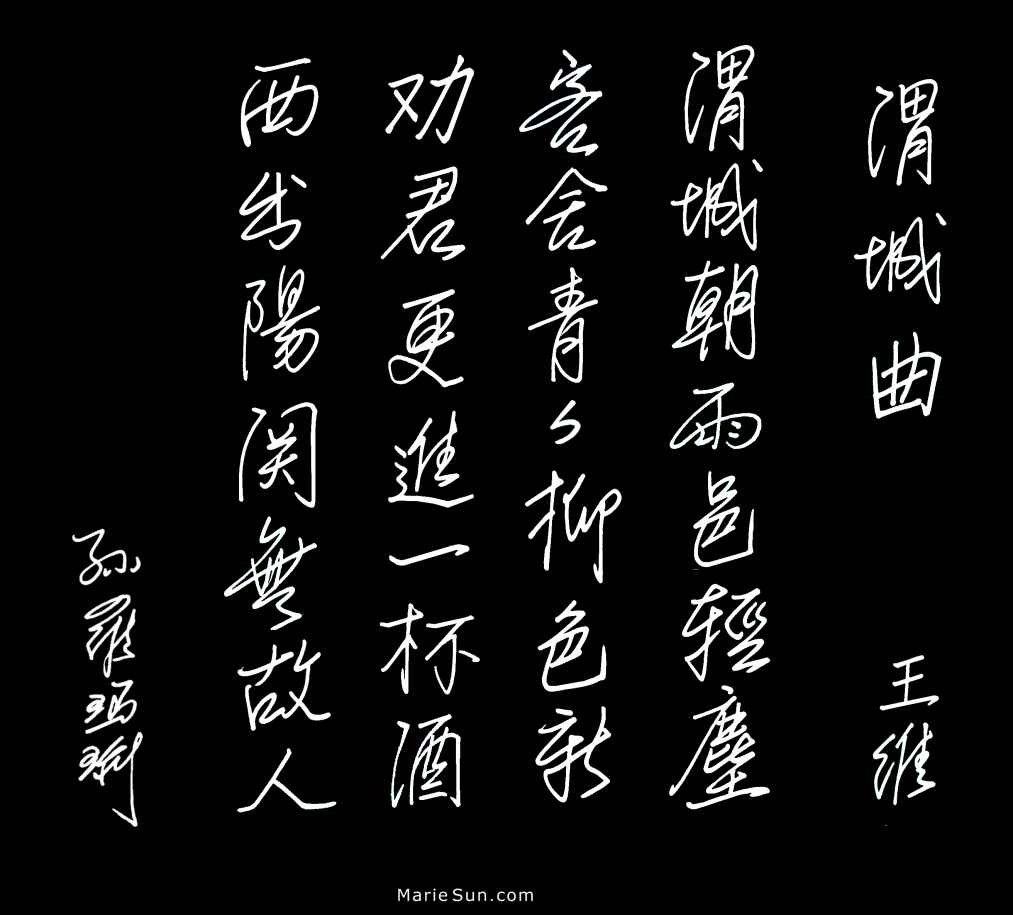

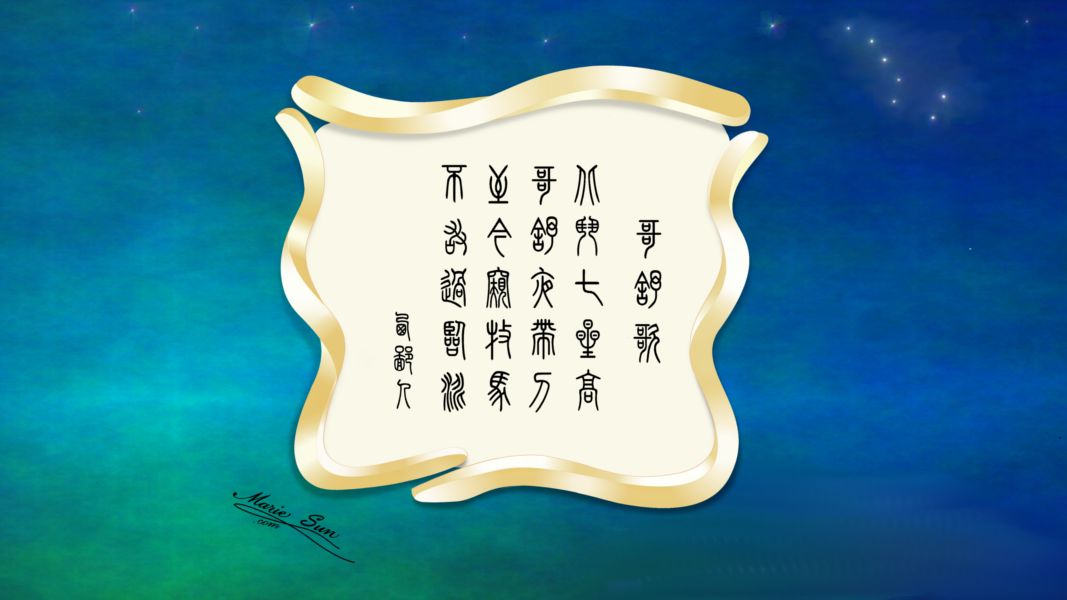

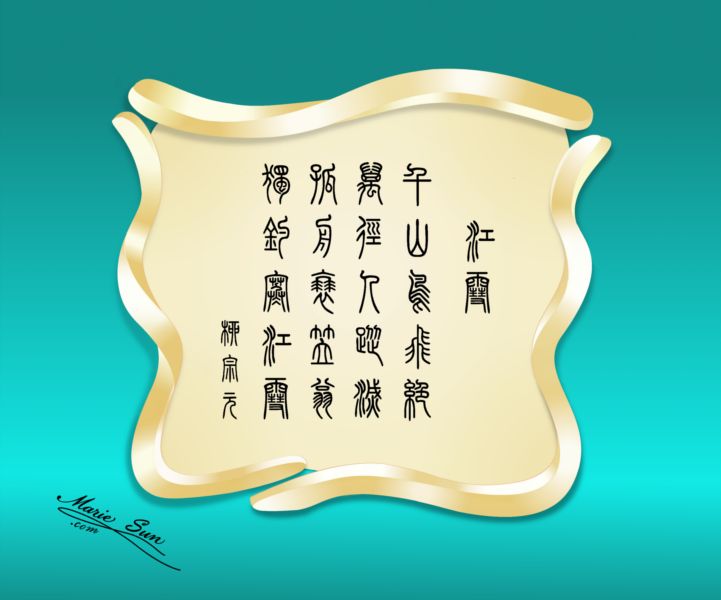

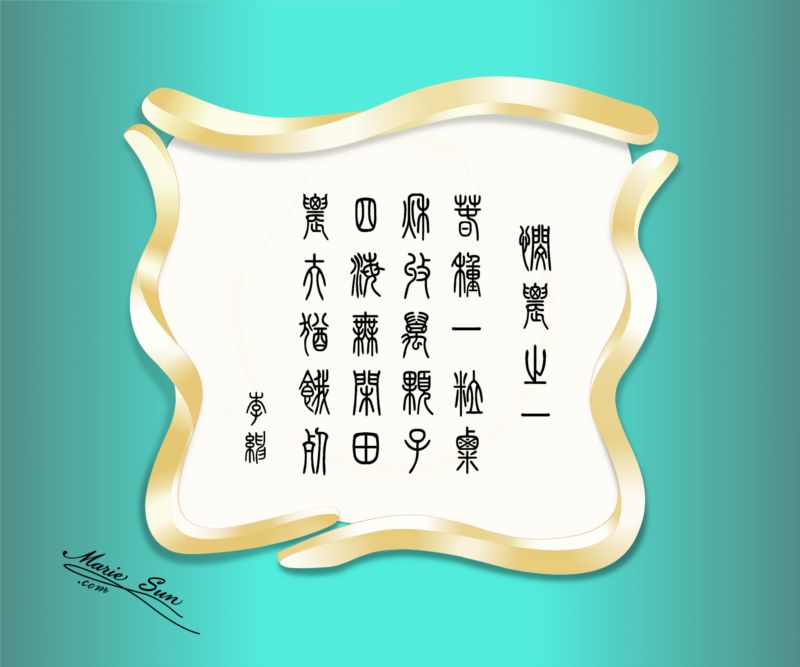

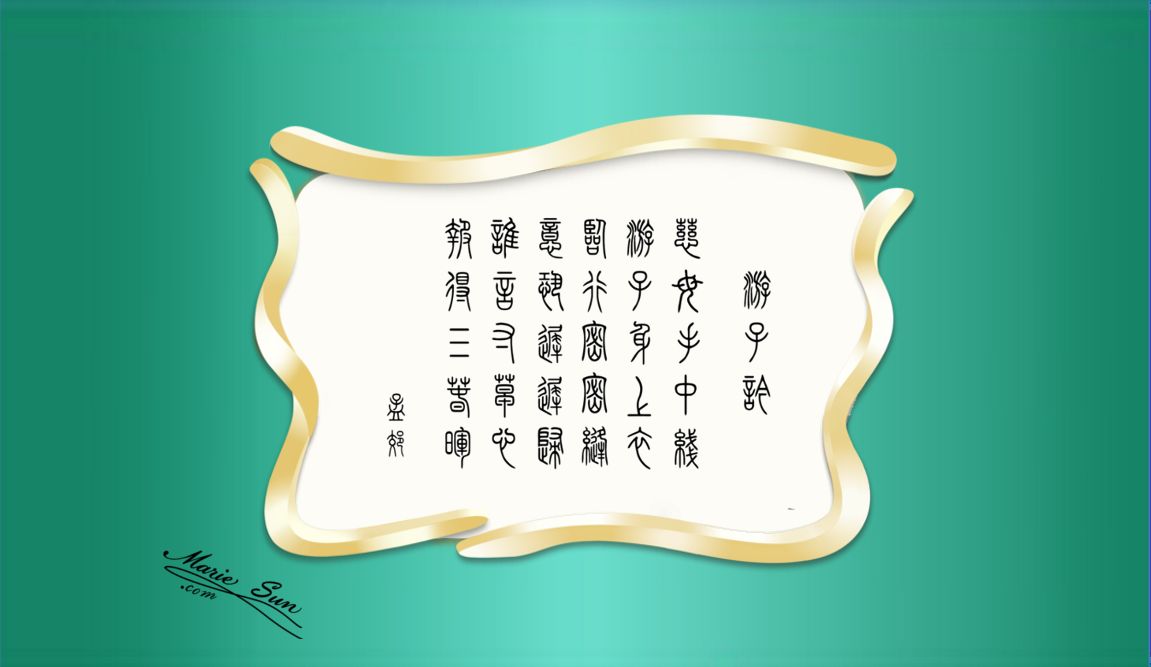

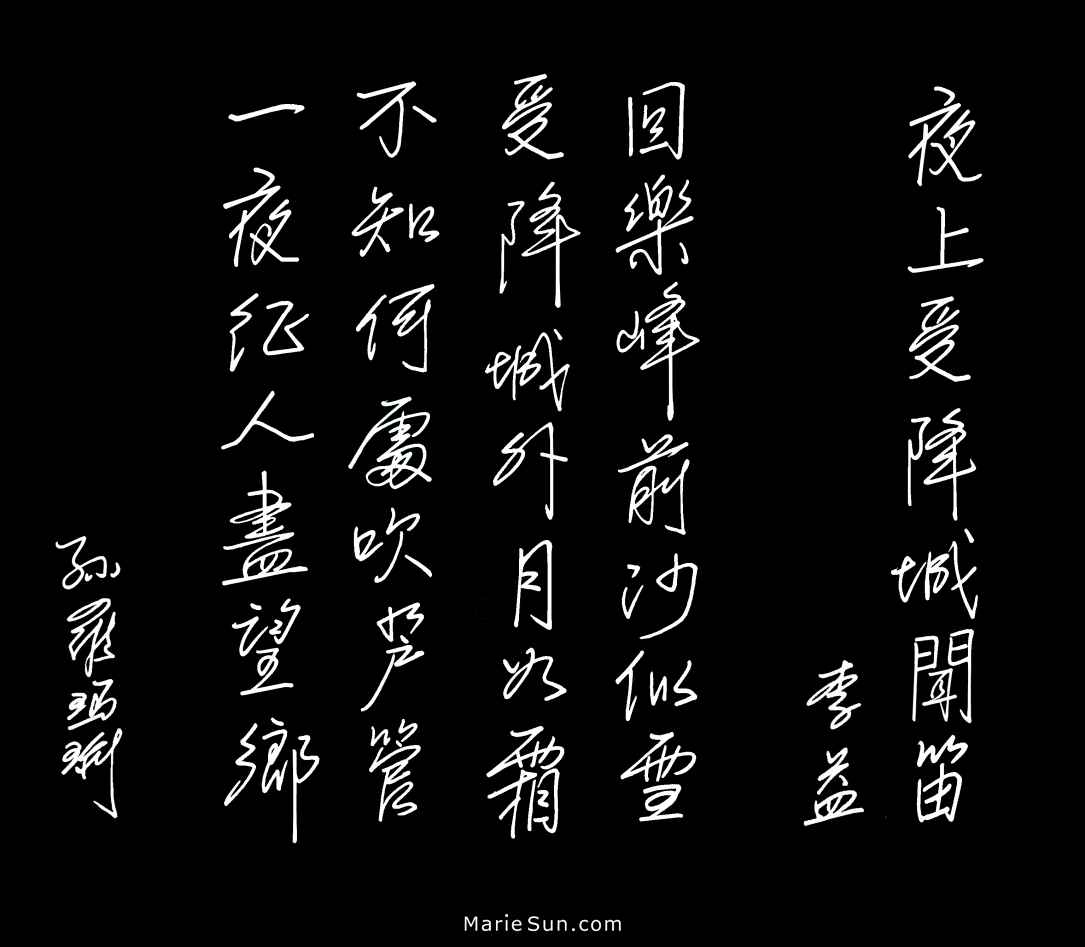

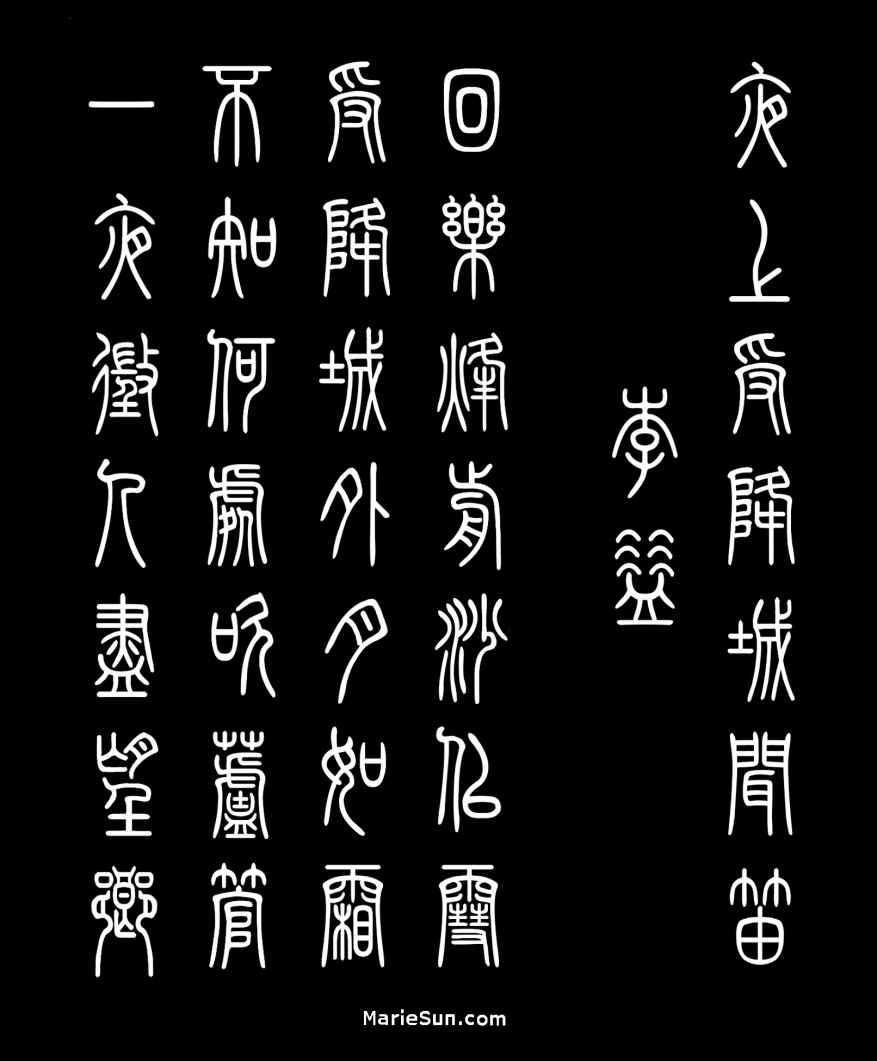

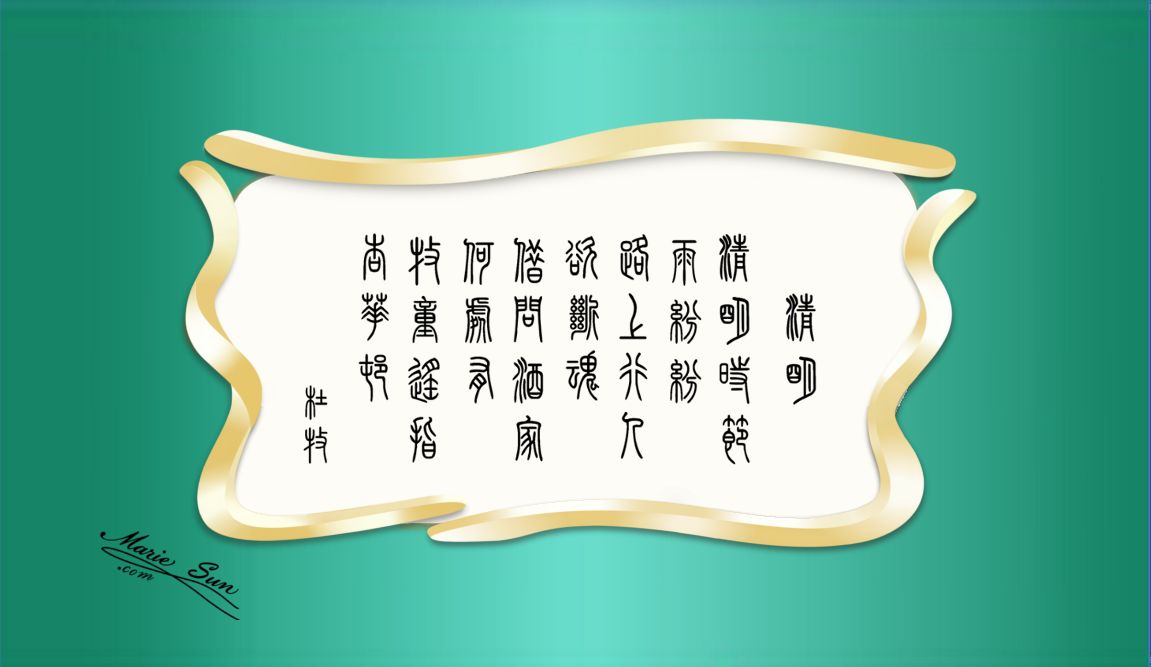

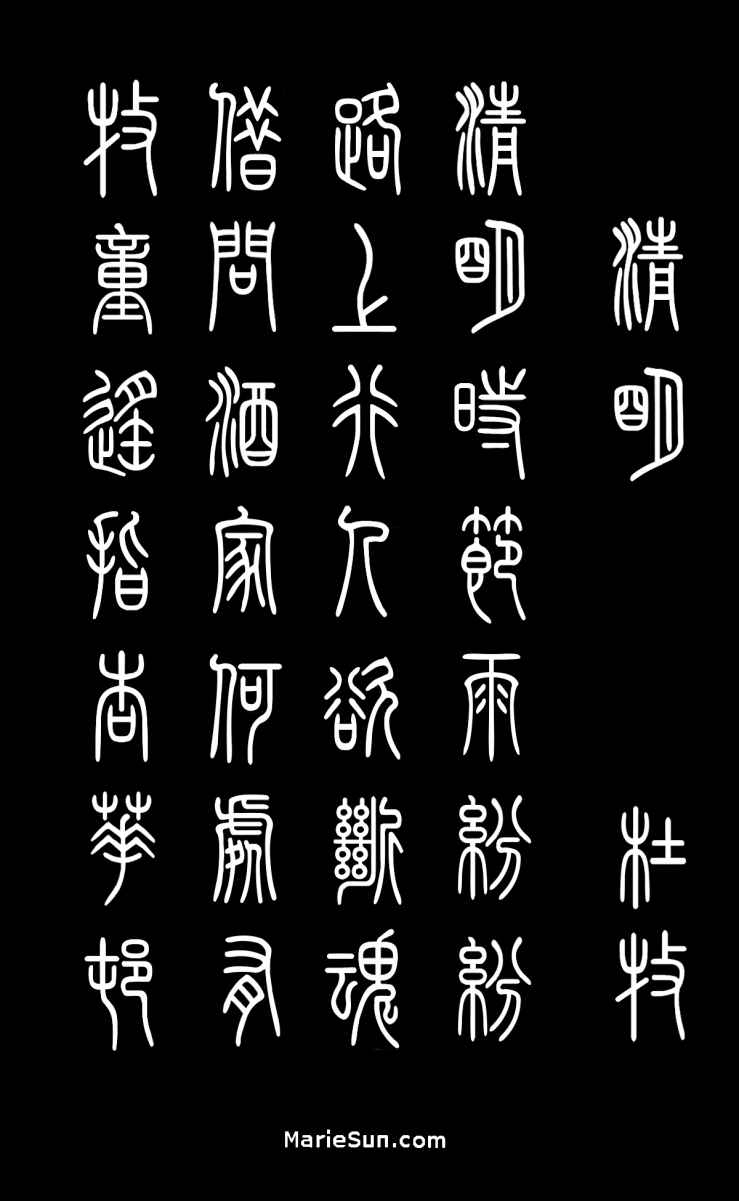

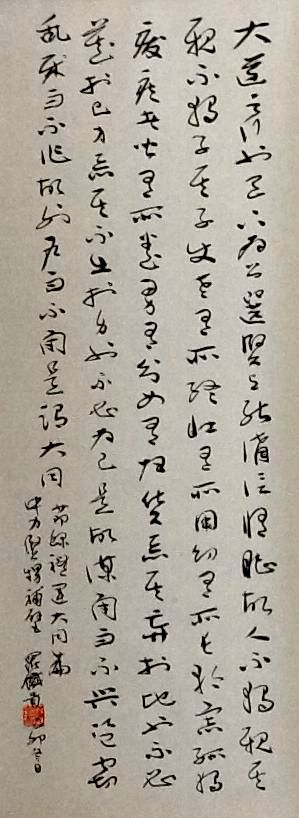

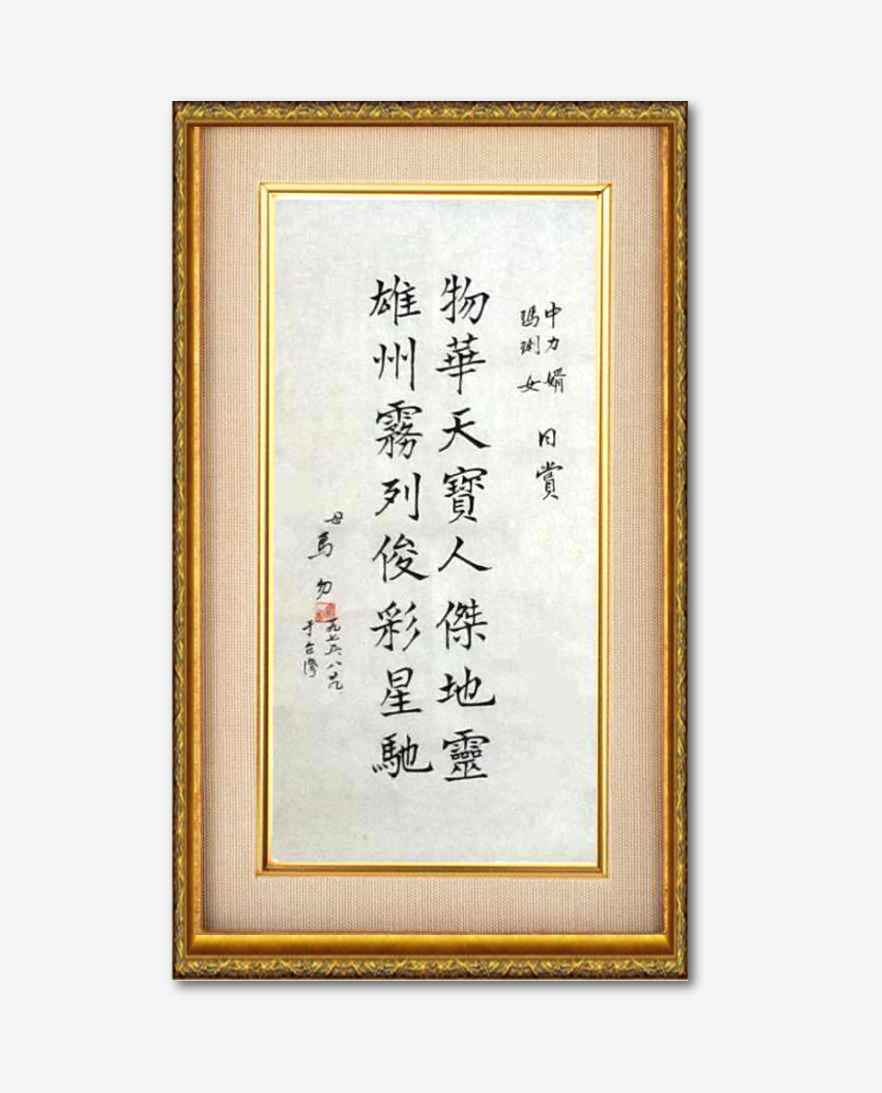

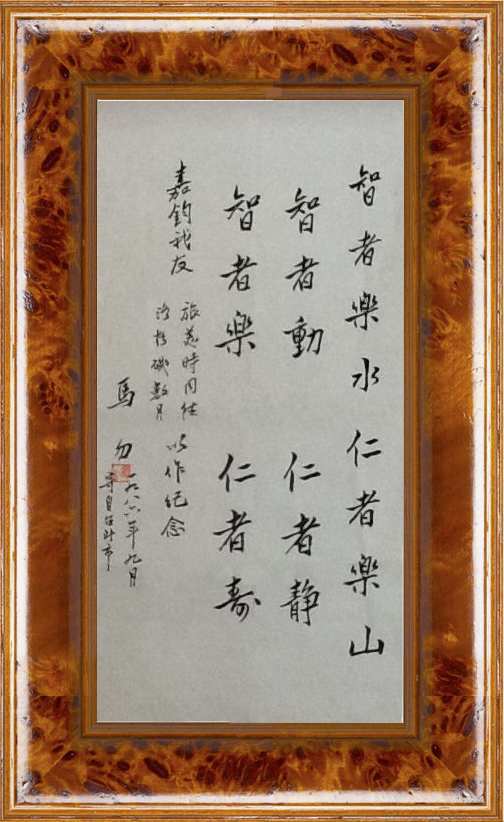

calligraphy in zhuanshu/zhuanzi 篆书/篆字 style

|

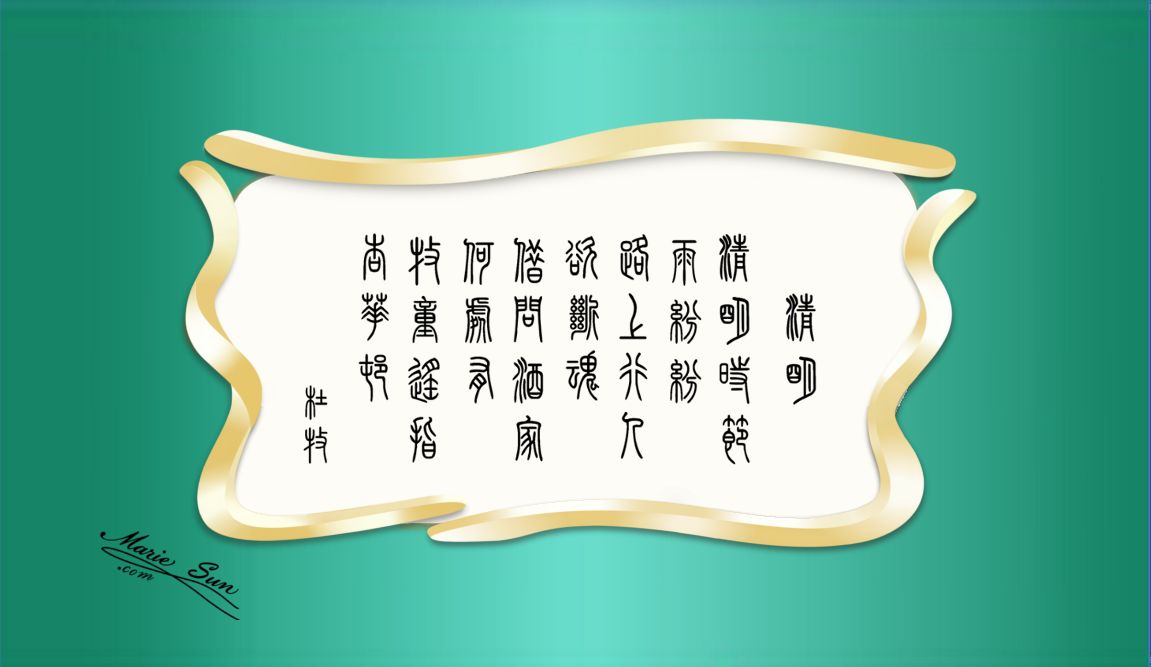

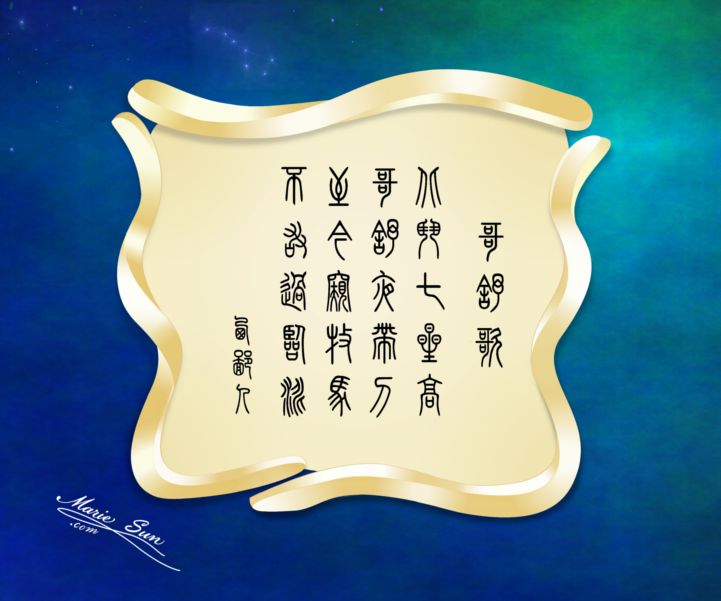

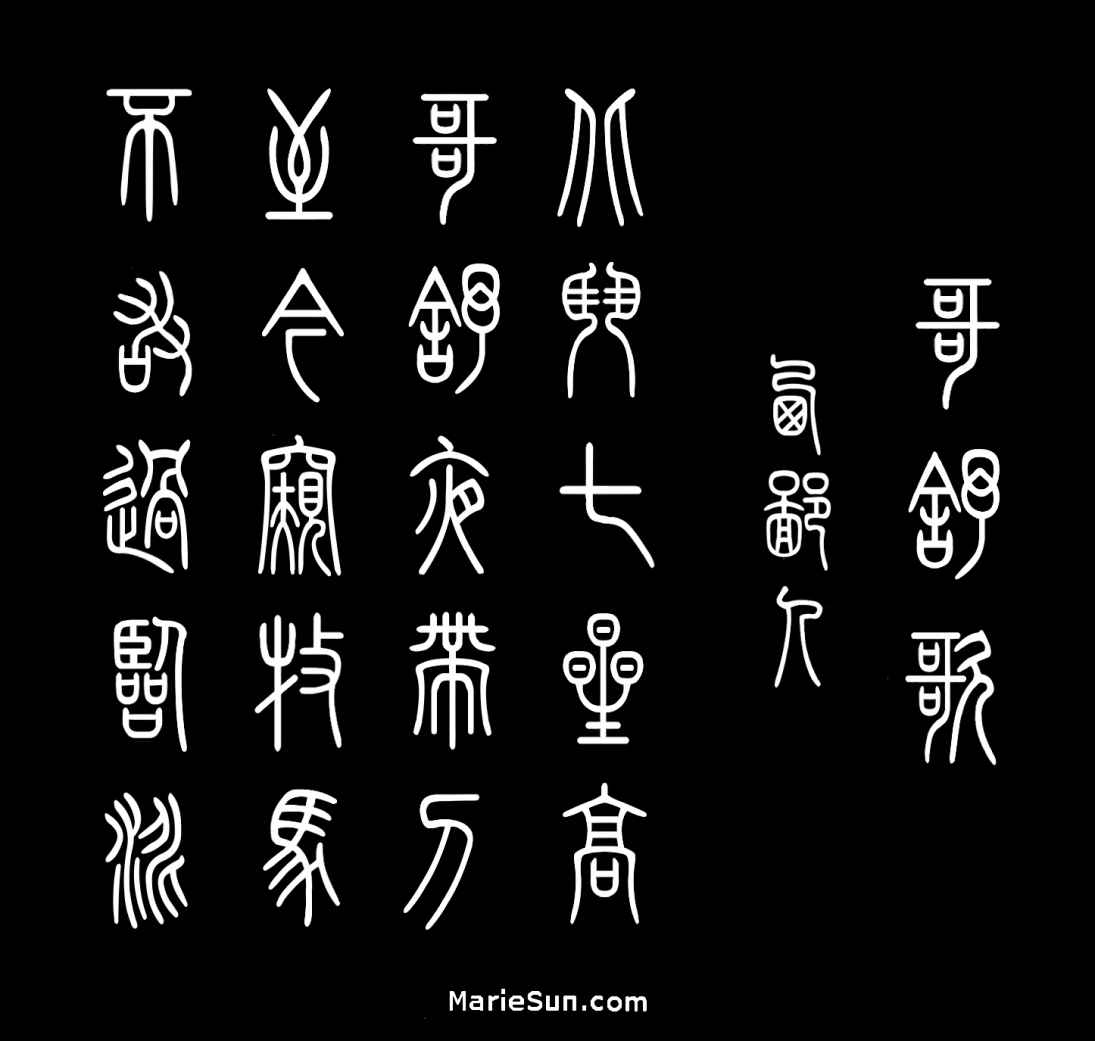

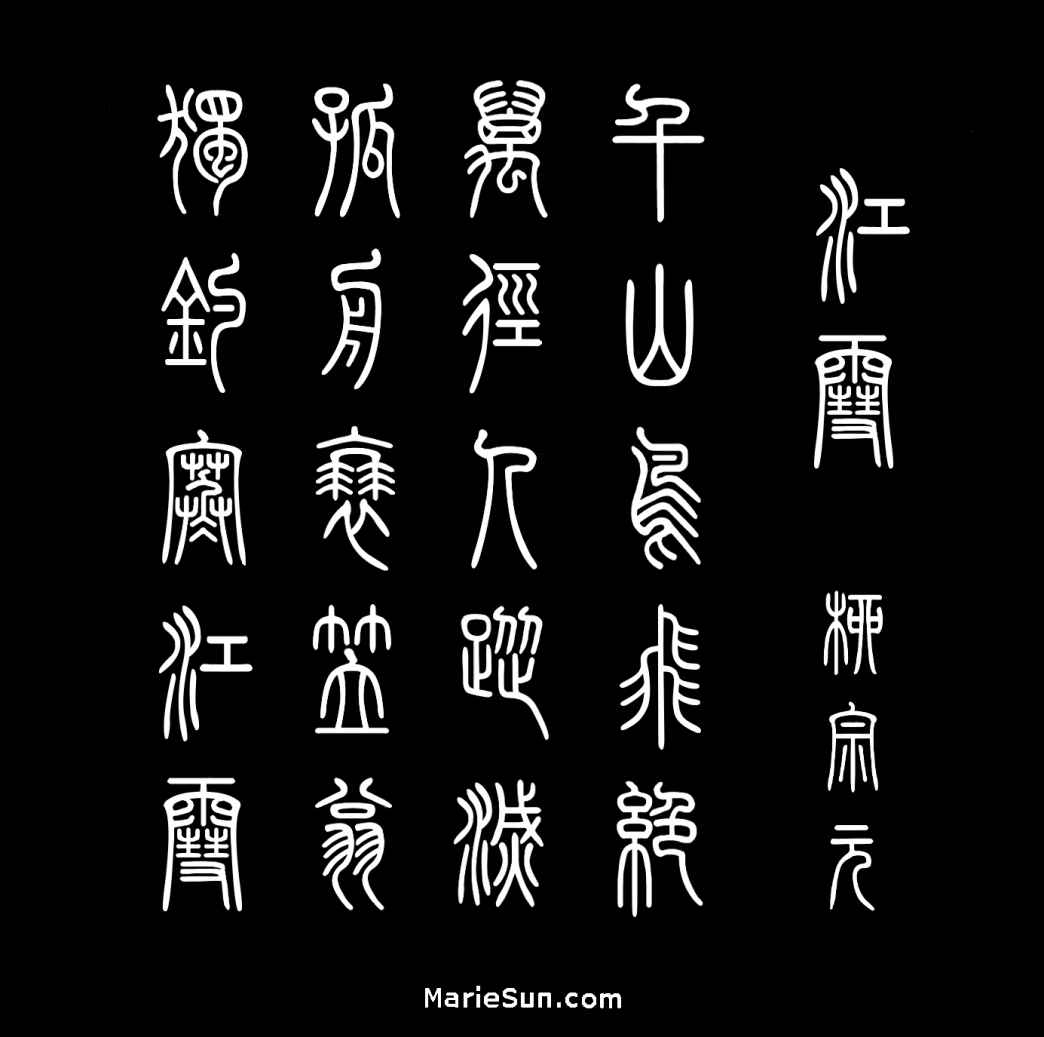

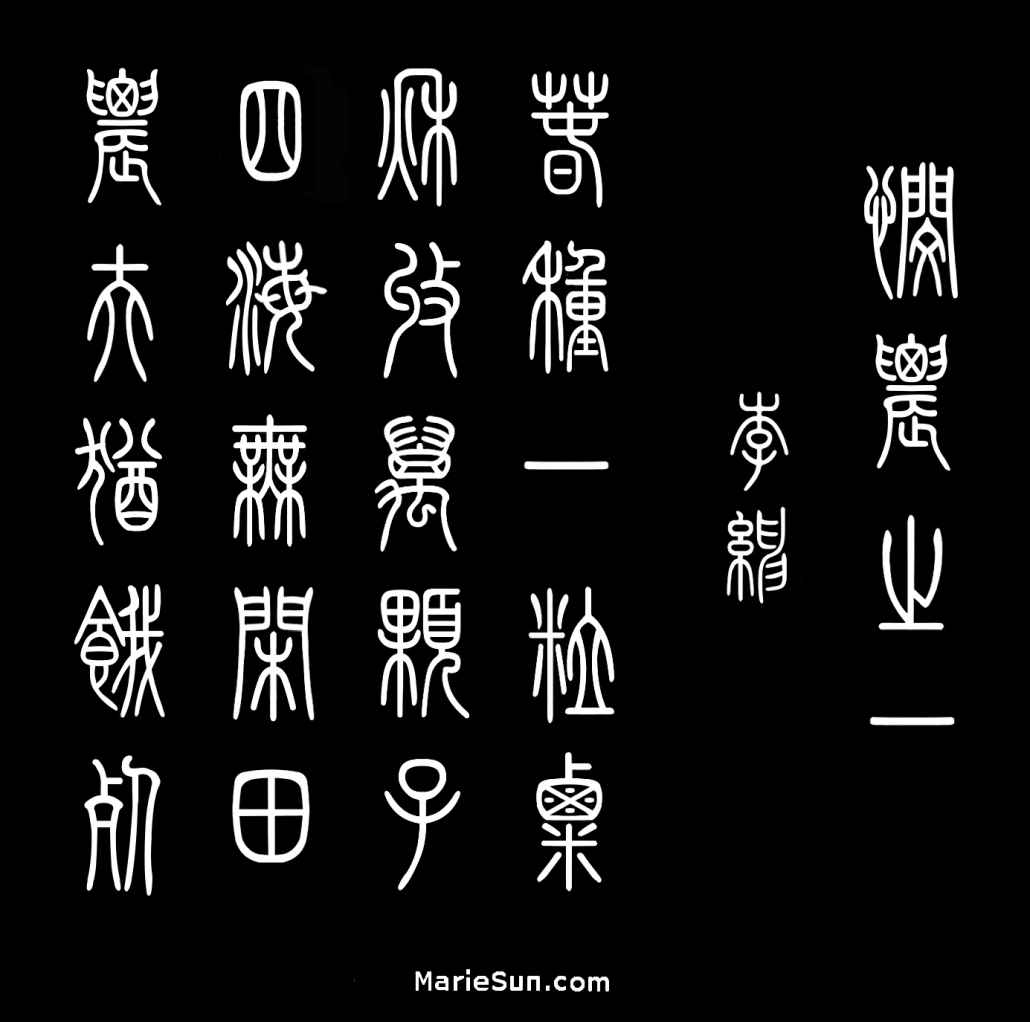

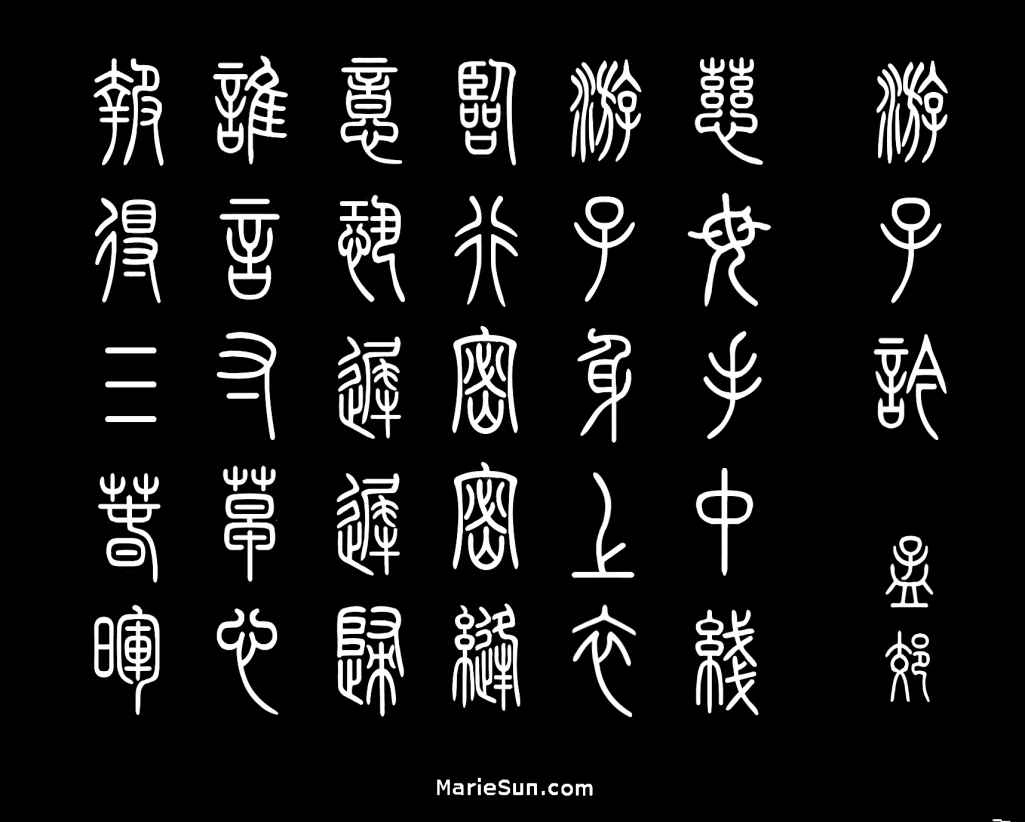

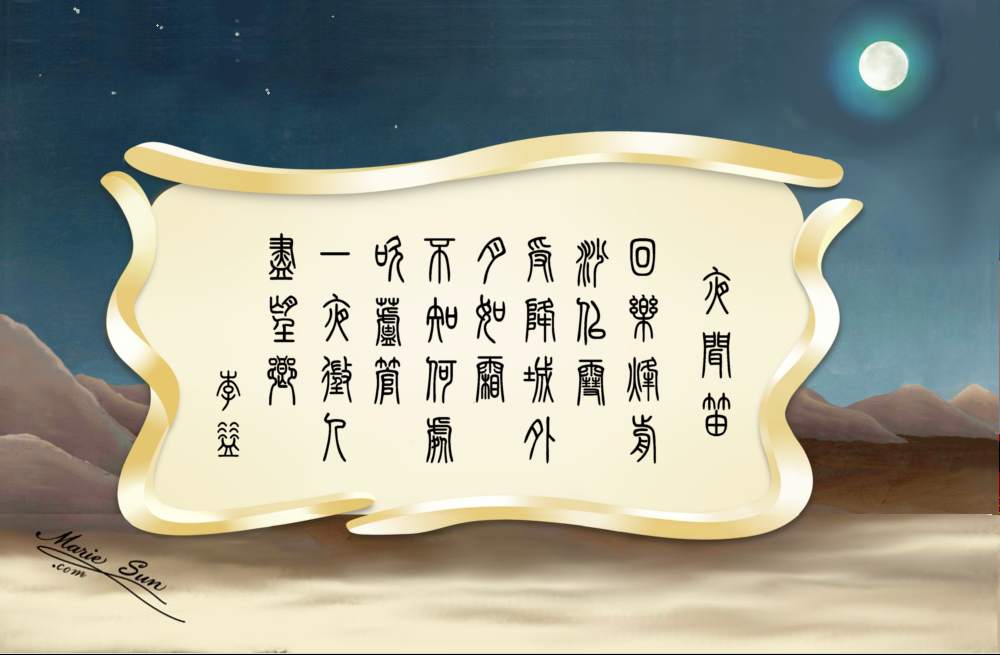

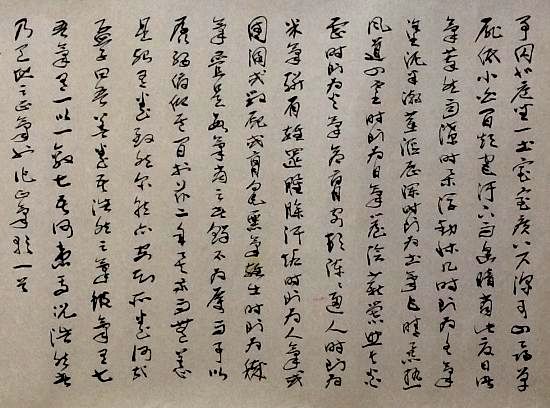

calligraphy in zhuanshu/zhuanzi 篆书/篆字 style

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|